This page last updated July 20, 2024

© Michael Kluckner

Jump to the section on the Hope-Princeton

highway

|

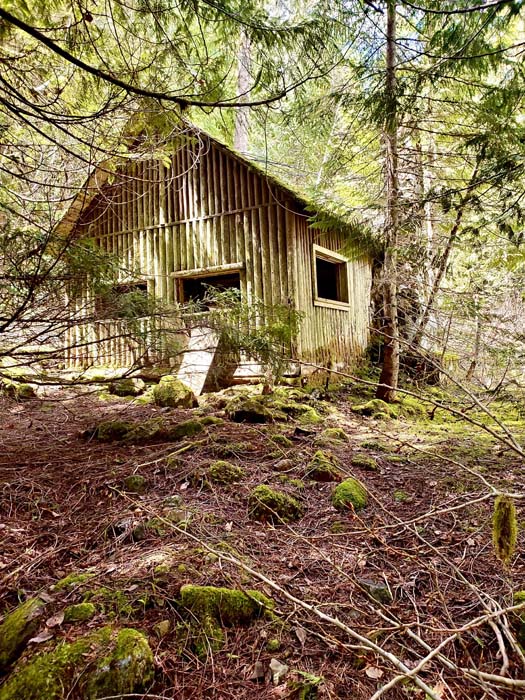

Above: Camp Defiance, late summer, 2000; right: another sketch in late November, 2002. It hadn't occurred to me until I did the sketch at right that Bill Robinson's little Shangri-la was in the blue gloom of the mountains from mid-November until February. No sun penetrates down into the valley for those few months of the year. |

|

|

Written in 2001: Along Sumallo Creek just inside Manning Park at Mile 22 on the Hope-Princeton highway, there stand two cabins that are gradually disappearing into the gloomy, damp underbrush. They have been abandoned for as long as I can remember (about 40 years of driving by them on the way to the Interior). They are of a quality beyond the typical drifter's shack, particularly the cabin with the stone chimney, indicating that the builder had some money and was intending to stick around for a while. The legend is that they were the accommodation for the Foundation Mine, which did some placer work and perhaps had a hard-rock mine back in the hills. It was better known as Camp Defiance, the home of Bill Robinson. Bill Robinson and the Foundation Mine aka "Camp Defiance" From Tom Hodgson, 2001: "I am a retired mechanic living in Cranbrook, British Columbia and was interested in your comments over the CBC this afternoon. I worked at Allison Pass from 1953 till 1961 and drove to Hope several times a week so although I never did leave the highway and go down to the cabins you mentioned they were the topic of conversation amongst the highways crew that I worked with so the information should be considered second hand but may serve to confirm some other impressions you have or will get. The inhabitant of the cabin was Bill Robinson who had been there since the First World War. (The Dewdney Trail went right past his door so he wasn't as isolated as one might imagine.) I don't know what mineral he thought he had but Canam Mine was a development just east of him and that was based on copper--as one was driving east at the 21-mile hill [just east of Bill's cabins] the clearing for a tramway was visible on the side of the mountain so at various times considerable money was spent on the development of the Canam property (but to my knowledge no ore was ever shipped). The existence of the massive copper deposits in the Copper Mountain area near Princeton was undoubtedly used by promoters to raise the capital for such endeavours. Foundation Mines had no such efforts at development. I often used Bill Robinson as an example to my kids of the reality that no matter how convinced you are or how sincere you might be if that confidence is not based on fact you can end up investing your life and not gaining your goal. One of the truck drivers was telling us that Bill had had a bad night – apparently a bear tried to get in his cabin one night so Bill took the frying pan and started beating on it. While he made noise the bear stopped tearing at the shakes on the roof but as soon as he stopped the bear started again so he hadn't gotten too much sleep. Bears in that area had learned the value of trappers' food caches and were smart enough to crush tin cans and suck the contents out so Bill's visitor had an idea of what he was after." Detail of map from Vanishing British Columbia Photo by Lucien Campeau of Camp Defiance in the 1950s or 1960s. The amateur historian Rev. John C. Goodfellow left an account of an encounter with Robinson during a hike from Princeton to Hope in 1929 [The Old Hope Trail by Rev. John C. Goodfellow. Museum and Art Notes Vol IV, No 2 June 1929 (Art, Historical and Scientific Association of Vancouver, B.C.)]: They were travelling east to west: "We had not far to go before we came to the Skagit trail, on our left [the 1858 Whatcom Trail to Belllingham]. After a while we crossed another bridge and came to the first real signs of civilization we had met since leaving the Overland [car] at Nine Mile Bridge. This was Camp Defiance, a comfortable log home, and a garden. We walked right in, and received a royal welcome from a man named Robinson, who proved to be a friend of Mac's [one of the party]. Our next objective was M. le Farge's cabin at 19-Mile (i.e. 19 miles from Hope). Le Farge is a little man with broad shoulders. Mac said he left France in 1884, came to New Orlenas, and eventually became a chief in some big establishment there. He was really glad to see us, and insisted that we stay for supper with him. He had had bad luck the previous year; wasted a lot of shot; the coyotes had robbed his trap-lines; and the "bugs" had played havoc with his little garden. But for all that he proved a good chef, and an excellent entertainer." [I don't know anything about Le Farge's cabin – I presume it's dust.] From Deb Ireland at the Princeton Museum, 2024: A link to Hiking the Hope Trail, 1930s Style, with delightful details about Goodfellow and his treks.

The legendary newspaperman Bruce Hutchinson wrote an article called "To the Okanagan in a Day" (Province Sunday Magazine, August 30, 1931, p.10), extolling the benefits of a modern roadway through the Hope Mountains. He was travelling east to west, and described his arrival at Camp Defiance: "We are descending now, but still by easy grades, and soon we are down beside the green waters of Sumallo. Here, on the boiling stream's edge, is the first house we have seen all day, the big log house of Bill Robinson, whom people call the old 'Flintlock of Sumallo.' "Bill Robinson's well-named Camp Defiance is almost the farthest thrust of civilization into these mountains. His little garden of strawberries, of lettuce and potatoes, his six petunias and eight Sweet Williams, in the narrow gorge between the mountain and the stream, are a welcome sight to those who have just come out of the wilderness. And so are the big, firm trout that Bill caught at his back door last night, and the pie made from his late-ripening strawberries." From Peter Flynn, 2003: I own an old Land and Forests map – it's about 1939 – which has the old Dewdney Trail, HBC Trail, etc. on it. This map was in a house that my parents rented in Hope on the Coquihalla River, which has since burnt down. On the map, there was printing in pencil on the Dewdney Trail, just past what is now Sunshine Valley, but it wasn't until I read on your site of the exploits of Bill Robinson that I was able to decipher the printing on the map as "Bill Robinson's Cabin." I found that pretty interesting. It is also very interesting, because in the Pioneer's book on Hope, called "Forging a New Hope," there is no mention of Bill Robinson or Mary Warburton. About twenty years ago, I did go down to Bill Robinson's cabins; there was a river rock fire place then, but I don't think there is much left of the place now. Note from Len McIver, 2004: I grew up in Hope, B.C. where my father, Leo F. McIver, worked many jobs on the highways in and around Hope in the 50's and 60's. His work as a driver for Henry Hockin Bulk Esso out of Hope and later for the Dept. of Highways out of Allison Pass, gave him intimate contact with the businessmen and pioneers that worked the Hope-Princeton corridor. In short, he became a friend of Bill Robinson - proprietor of Foundation Mine. I can remember going out to the cabins on weekends where Bill and a number of cronies (Dave & Marg Campbell, Grant & Hilda Gibson, Bert Scott and another trapper/prospector Bill Jamieson - who also had a lovely cabin on 9 mile hill, wiped out in the Hope Slide in 1965), along with my dad and mom, would tell stories, fish, drink and dream. I remember pulling off Hwy 3 at about 21 mile on a slight bend on an upgrade, then driving into the bush on a narrow road with branches slapping both sides of our vehicle; then crossing a very narrow log/plank bridge...then driving maybe 1/4-1/2 mile on the other side of the creek to the site of the buildings. As one of your other commentors on this piece, I too remember 3 buildings... a cook/bunk house, a wood/storage shed and a cabin (possibly Bill's old cabin?). We sometimes stayed over-night burning coal-oil for the lamps and wood in the rock fireplace. During the days we fished or picked huckleberries (depending on the season). While searching through my father's WWII "stuff" (at the time of the Juno Beach celebrations), I came across an old share certificate of 500 shares of Foundation Mine. I remember dad having it back in the 60's and was pleased to see that I had kept it with his "stuff" after he passed away in 1972. And, as it turns out – thanks to Len McIver for locating them – photos were long ago collected and published about the bachelors and eccentrics of the area . . . . Photographs from "Forging a New Hope", published in 1984 by the Hope & District Historical Society *** From ARLO GIARDINI-BLUM, Adventurer, Explorer,

2022: I am an amateur historian, adventurer. I frequently

bushwack/hike/4x4 to old mines, cabins , areas of interest here

in BC when I have time.

From Adam and Chyanne, Adventures R Us, 2020: a cool video on YouTube showing them wading the creek and bushwhacking in to the remains of Bill Robinson's cabin: https://youtu.be/k-y2FBOKC8k From Craig Wilson, 2015: After driving past the Robinson cabin twice a month for almost 2 years i figured i should stop and check it out while the river is still passable! The river was running fast and the water was cold, so i figured i should seize the opportunity as in another month or two it may be faster and colder still. i took some pictures of the out buildings and the interior of the cabin. The cabin is still going strong. You can tell it was built to last! as previously mentioned, the outbuildings didn't suffer as well due to that slide. I was surprised to see actual plywood in there. I guess i thought it was older. that slide is impressive too. you can see how far it came down the mountain.

Update September 2013: After hearing from Todd Lester (below), I went by for the first time in years and found ... ... a memorial bouquet of plastic flowers, with the slide path high up on the mountain in the background, and ... the main cabin still standing in the

thicket, so it was just missed by the slide. From Todd Lester, 2013: I thought that you would be interested in knowing that there has been some natural occurring damage to the lower building at Camp Defiance. We noticed that, upon passing the site on May 15th, a small landslide has cut directly through the site and destroyed the smaller building. There are remnants of it just above the river bank, but for the most part, it is gone.

From Merlin Williams, 2011: My dad's signature (Al Williams) appears on the photo of a share of Foundation Mines on your site. He, my mother (Anne Williams) and Bill were great friends and we many times stayed at Bill's place, fished in the river, etc. I helped do some of the last surface drilling ever done for Foundation Mines before it closed down due to the park. The main site for exploration was up the mountain and on the other side of the Hope Princeton Highway from the camp. Note from Andrena Ryznar, 2003: I have a cabin at East Gate just outside of Manning Park and I have passed those cabins thousands of times over the past 30 years. I do however wonder if you can confirm something for me. My memory is not great, but I do remember there being three cabins, not just two. My father may even have a picture of them. I have also seen a picture of them in an issue of Beautiful B.C. magazine, but that was probably at least 10 years ago. If you find anything out about the third cabin that was more toward the creek that runs in between the cabins and the highway, I would be very grateful. The

Hope-Princeton Highway, etc. 2013: Jeff at ClarkGeomatics.ca sent along a copy of his new Manning Park/Skagit Valley map, which includes sites identified in "Vanishing British Columbia."

From Susan Marles, 2012: My father, Doug

Willis (later of Willis and Cunliffe Consulting Engineers), was

the chief surfacing engineer for the dep't of Highways, he was

one of the engineers who surveyed and designed most of the

postwar B.C highways and some major bridges during the period

1948 to 1964.

Allison Pass Gateway

2. Politicians (L to R), unidentified, “Boss” Johnson (B.C. Premier, Liberal), E.C. Carson, Minister of Highways.

Overview of attendees. Identified: just rear of Mr. Harry Hayne (in the white hat, also a civil engineer) Neil McCallum, supervising civil engineer talking to his assistant and project engineer for the Hope-Princeton project, D.T Willis (my father).

Presentations to the honorary guest, Charles Bonnevier, whose pack horse trail was the foundation for the route for the highway over the summit and into the Similkameen valley. Premier Johnson on the left, E.C. Carson on the right. Mr. Bonnevier unlocked the gate.

Equipment display for highway maintenance

and the line-up of cars waiting to take the first drive. **** Forest fires were a regular occurrence in the Hope-Princeton area, and bedevilled travellers on the Dewdney Trail including Susan Allison, who remarked on her narrow escape from one in her memoirs (A Pioneer Gentlewoman in British Columbia: The Recollections of Susan Allison, ed. Margaret Ormsby, UBC Press, Vancouver, 1976.) The most notorious fire in my memory swept through the valley below (to the west of) Allison Pass in the late 1950s, prompting the erection of the "gallows," which lasted for years, and a burnt-over landscape that took nearly 40 years to heal. Postcard by the Coast Publishing Company, Vancouver, about 1960, photographer unknown. The Dewdney Trail The Hope-Princeton highway didn't open until November 2, 1949, but trails had existed across the mountains for millenia. The Dewdney Trail, just north of the 49th parallel from the expansionist Americans, was actually the second one post-contact (or the third one if you count the Hudson's Bay Company's brigade trail that crossed the mountains further north, intersecting with the Fraser River at Spuzzum). The earlier trail, Alexander C. Anderson's route of 1845, went from Hope via the Coquihalla, Nicolum, Sumallo and Skagit Rivers, then up Snass Creek to a small lake that Anderson named the "Punch Bowl." From there, he followed the Tulameen River through Paradise Valley, eventually joining the Similkameen River at the present site of Princeton, then known as Vermillion Forks. The Dewdney Trail was commissioned by Governor James Douglas in 1860 in response to the discovery of gold in the Okanagan-Boundary region--an area much more easily accessible from the USA than it was from the only British population centre at New Westminster. Edgar Dewdney was an English civilian surveyor only three months in the colony, hired to blaze the trail under supervision of the Royal Engineers. Dewdney eventually extended the trail all the way to Fort Steele in the east Kootenays following the 1865 gold rush there, but that portion of the trail saw little use as the supply routes running north from Washington were so much simpler. Riding the Dewdney Trail through the Hope Mountains soon after its completion, Douglas wrote that the journey could without exaggeration be compared to "the passage of the Alps." [James Douglas papers, British Columbia Historical Quarterly, vol. 2, 1938, p.81] Among the significant historic personages who used the trail were, in 1883, General William Tecumseh Sherman leading a party of 81 including a military escort of 60 men, 66 horses and 79 mules, who crossed BC in order to reenter the US to subdue Indian uprisings in the American Northwest.Some years later, a hunting party consisting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, with 6 gentlemen and 6 servants and a train of 14 saddle horses and 10 pack horses provided by Thomas Ellis of Penticton, used the trail; the archduke's assasination in 1914 sparked the declaration of the First World War. [The Dewdney Trail, by Kathleen Stuart Dewdney. Okanagan Historical Society Report, vol. 22, 1958.] The Dewdney Trail followed the Coquihalla River for a short distance east of Hope, then swung southeast along Nicolum Creek. At the headwaters of the latter, it crossed a divide (the Hope Slide and Sunshine Valley-Tashme area), then followed Sumallo Creek southeasterly past the Camp Defiance site. According to Old Park Trails in the Proposed Cascade Wilderness (Okanagan-Similkameen Parks Series, 1978), the Dewdney Trail followed Snass Creek and passed to the north of Snass Mountain, while the later Hope Trail followed Skaist Creek and passed to the south. Both used Whipsaw Creek, on the eastern side of the mountain pass, to reach the Similkameen and the rangelands to the east. Bob Pelley, whose Pelley Ranch was a landmark on the "5-Mile" northeast of Princeton, drove cattle over the Hope Trail as late as the 1940s. More than 40 years after the initial trail was finished, in 1901, Premier James Dunsmuir commissioned Dewdney to again survey a path through the Hope Mountains, this time for a possible route for a railway. Dewdney looked for easier grades, following his old route until he got to Skaist Creek, but then continuing southeast along the Skagit and crossing Allison Pass. He then descended Memaloose Creek to where it joined the Similkameen River, and from there followed the latter all the way to Princeton. Dewdney's 1901 survey is the route followed by the Hope-Princeton highway. Allison Pass is named for John and Susan Allison, who used the Dewdney Trail in the 1860s and 1870s to reach their homestead near Princeton. Curiously, my oldest map, a 1914 provincial government Lands Department map at a scale of 4 miles to the inch, shows no established trail through Allison Pass. But it does show (as well as the Dewdney Trail) an established trail running along the Similkameen River all the way to Princeton from the area that today is the Manning Park headquarters. Interestingly, this trail continues due west from Cambie Creek through the Gibson's Pass (today's cross-country and downhill skiing area in Manning Park), then descends Nepopekum Creek on the south side of Steamboat Mountain (past an intriguing dot on the map called Jarvis) before swinging to the northwest along the Skagit River, then heading upstream along the Klesilkwa River to its headwaters, crossing yet another divide before picking up Silver Creek, which descends through the mountains and drains into the Fraser River just west of Hope. The 1914 map shows quite a number of preemptions, indicating perhaps some attempts at settlement, along this very southerly route. Note from Steven Henslow:

My memories of the Hope Princeton highway go back to the days

when it was a dirt road - they were just starting the

construction of the PAVED WOW highway in 1950. I remember that

mine well I recall seeing the people and I have climbed up to

the old "diggings" you can still get some gold if your patient.

I read an interesting passage in Mrs. Alison's diary about how

she had dinner with General Sherman. I have spent a great deal

of time trying to trace what he was doing here. My father was

the manager of an insurance company that was insuring the many

mines and logging camps in the province inspecting for

liability, and fire insurance. Some of my wife's relatives grew

up in Hedley. I got some great stories at a family reunion a

couple of years ago. I was also one the last people to see the

famous Phoenix hotel before Granby mines destroyed the rest of

the town. My interest in B.C. history goes back to 1951 when my parents

bought a piece of the Lacey Ranch in Osoyoos. We were fortunate

to come to know the Lacey's well and I spent many nights

listening to Mrs. Lacey tell stories of live in Phoenix - they

bought the ranch after the Phoenix copper mine shut down . I am

currently am researching one of Phoenix's more colourful

characters that I recall Mrs. Lacey talking about it was either

John or Patrick O'Shea. When we told her were were going up to

Phoenix she asked that we please check his grave and let her

know if we could find it. We had no problem finding it. She

proceeded to tell about him - the Bo Jangles of Phoenix I would

call him. There was not a lady in town that did not want to get

on a dance floor with him. He was forewman who was killed in one

of the too many accidents that happened in those days. Just think of this. A boat load of silk is spotted at the head

of the Alberni canal. Bon fires are lit along the canal to let

the CPR know a shipmentof silk is arriving. A train special

"silk train" is ready to meet the boat. Guards are notifed to

guard every crossing as the NON STOP train travels to Halifax.

The silk is sent to Paris and made into gowns. Those gowns are

shipped back to Phoenix - along with Champagne and other

delights, for the annual ball every year. The great battle at

Midway is another great B.C. history piece, along with how 5

Crows - chief of the Cayuse saved the northern section of the

Columbia River from becoming part of the Oregon The search for Mary Warburton Bill Robinson was known to all the packers and hikers who used the Dewdney Trail. His name appears in the accounts of the one great event that happened to the Dewdney Trail in the 20th century--the search for hiker Mary Warburton. Mary Warburton came to Canada from England in the 1920s when she was in her late 50s, and settled in Vancouver where her brother lived. She was a nurse, working mainly in private homes. In August, 1926, she completed a long nursing session with a terminally ill patient and decided to take a working vacation as a fruit picker in the Okanagan. She determined to walk from Hope to Princeton and camp along the way. Wearing a khaki shirt, breeches and a wide-brimmed hat, with sturdy canvas shoes, she arrived in Hope on August 24 and discussed her plans with the local provincial policeman, then left behind her groundsheet to lighten her load as good weather was forecast. She apparently despised overeating, so carried 4 packets of Ryecrisp, a half pound each of bacon, butter and cheese, a pound of raisins, 2 oz. of almonds and some tea, plus a pack of cards. Her estimated hiking time was 3 or 4 days. A frying pan, a billy, a spoon and a single-bladed pocket knife, plus a sketch map of the area and a compass, completed her kit. On August 26, according to writer Joan Greenwood, "she came to Bill Robinson's cabin, 23 miles from Hope. It was early morning and Bill was still in his bunk. She rapped on his door but did not wait for an answer and by the time Bill had pulled on his trousers and opened up he was only in time to see her brisk figure disappearing towards the east. Later, while investigating a mining claim, he saw her footprints near Snass Creek." Days later, after hearing of her disappearance, he compared notes with another prospector named White who had also seen her. A packer named Alf Allison had passed her on the way out and expected to catch her up on his way back to Princeton but missed her; he reported it and a search began, joined by Miss Warburton's brother from Vancouver. On September 16, three weeks after she'd last been seen, a four-inch snowfall covered the mountains. Eventually, after becoming hopelessly lost in the Paradise Valley area, she stumbled onto the cabin--"a rough cedar slab shelter"--of a Princeton oldtimer known as Willard Alfred "Podunk" Davis. He had left matches inside a piece of paper in a tobacco tin in the cabin. Desperately wet and cold, she lit a fire but managed to set the shack alight. Evidence of the recently burned cabin rekindled the search for her (sorry about the pun), and eventually she was found by Davis and Const. Dougherty of the Provincial Police. [The amazing story of Nurse Mary Warburton: survival and rescue in the wilds of B.C. by Joan Greenwood, Okanagan Historical Society, vol. 46, 1982] The area of the Paradise Valley near the headwaters of the Tulameen River has been named Warburton Park, and there are interpretive panels in the Manning Park headquarters office. Podunk Creek drains into the Tulameen River nearby. From Les Needham, 2014: Mary Warburton, who was lost on the trail from Hope to Princeton was my Great Aunt. In 1931 she was again lost in the Squamish area and never found. At the time I believe she was living in Vancouver with her Brother. Have you any idea of her brother’s name? From Kim at James Bay Coffee and Books in Victoria: I am the great-great niece of Podunk Davis, who's brother Pete was my great grandfather. My name is Kim Elizabeth Willoughby and I own a used bookstore/coffee shop/music venue in Victoria. Podunk keeps an eye on the main room for me. He's in the original frame that I rescued from my parents garage and dusted off.

Further historical notes on the Dewdney Trail Fur Brigades from the districts of New Caledonia in the north, the Thompson River, and Fort Colvile in the south, comprising 400 or more horses, converged on Fort Hope, which was established in 1848, two years after the signing of the Oregon Treaty with the US. As the brigades had to be rerouted away from the Columbia, which had become American territory, the Hudson's Bay Company had them converge on the Fraser. In 1846, A.C. Anderson, in charge at Fort Alexandria, was ordered to find a suitable route from Fort Kamloops to Fort Langley. He first explored the chain of lakes and possible routes between Lillooet and Harrison Lake; then, he returned via the Fraser, following the Coquihalla for 23 miles before turning southeasterly to ascend Nicolum and Sumallo creeks as far as the Sumallo's junction with the Skagit. (A Pioneer Gentlewoman in British Columbia: The Recollections of Susan Allison, ed. Margaret Ormsby, UBC Press, Vancouver, 1976, page xiii)

---------------------------- Hope itself has a very active arts

community, gallery and museum. See the Hope

Chamber

of Commerce site for details on events and opening hours. |