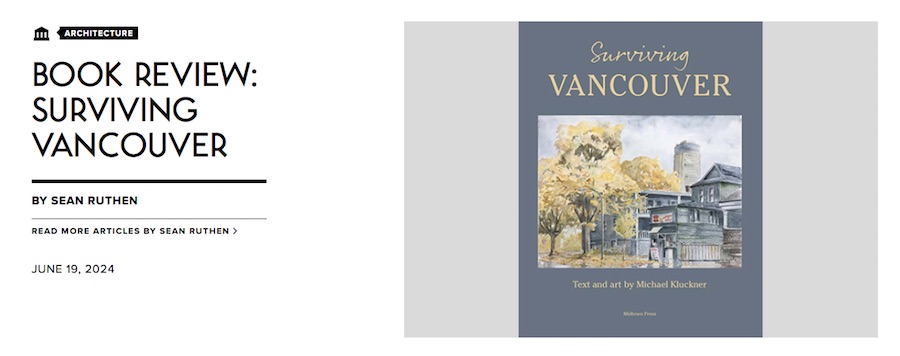

Surviving Vancouver

Return to home page Return to Books page

$25

| The book asks and attempts to answer two

questions: What's survived in Vancouver? And, how do you survive

within Vancouver, or without it? From historic neighbourhoods

under threat from land speculation to the debates about densifying

and making room, I explore the contested space of Metro Vancouver,

using some watercolour images from about 25 years ago as well as

new art with a more political edge. Its publication marks 40 years

since my Vancouver The Way It Was of

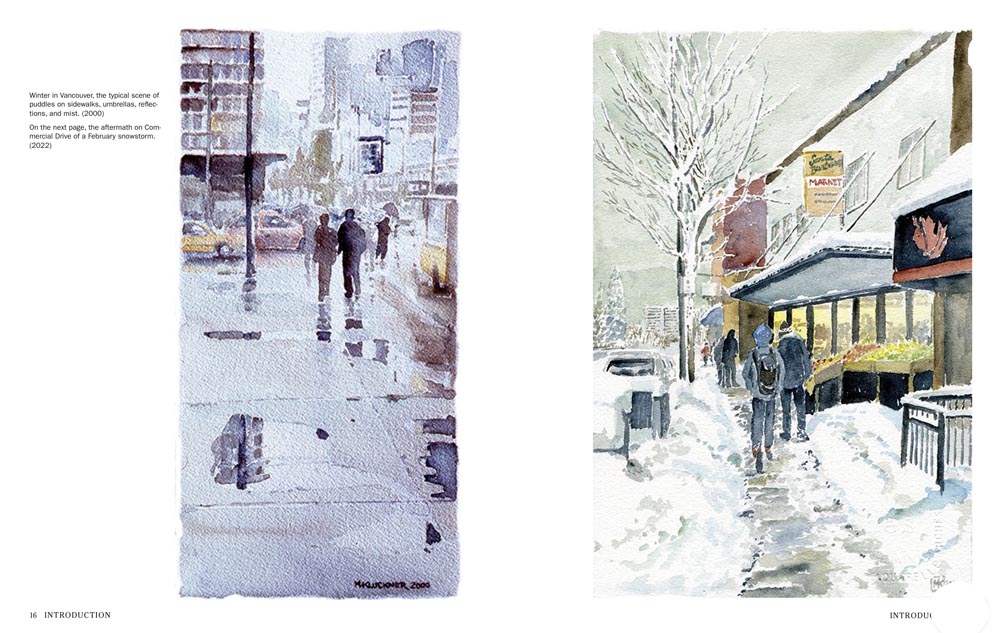

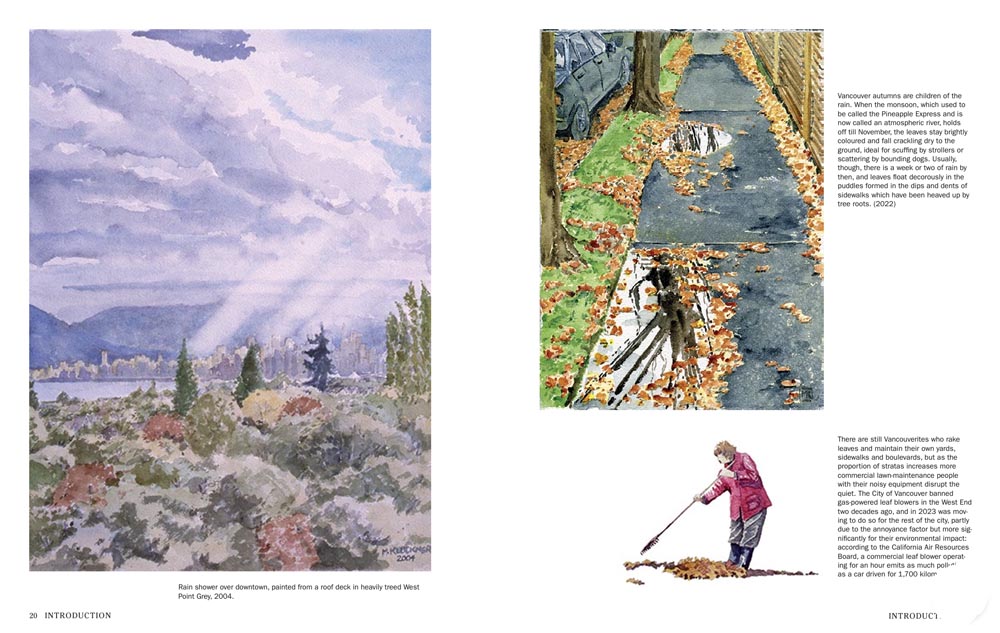

1984. The book will be available in stores from the beginning of April. Please support your independent bookseller! If you can't source it locally, I will ship it, but because of the book's weight (650 grams) the cost of shipping will be $20 in western Canada. I will get a quote for shipping it to the East and the US upon request. Contact me for further information or to send an etransfer. There is a page with some of the artwork from the book here. Here are a few page spreads: At the beginning of the book there are images of the seasons and the weather: |

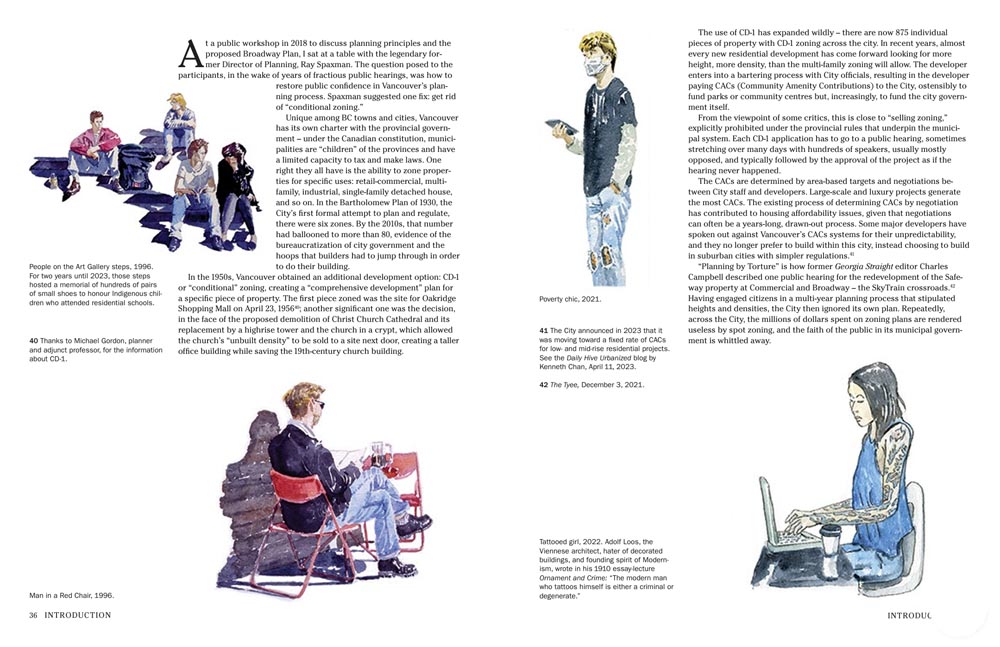

I've reprinted some of my people images from "Michael Kluckner's Vancouver" (1996), and added new ones....

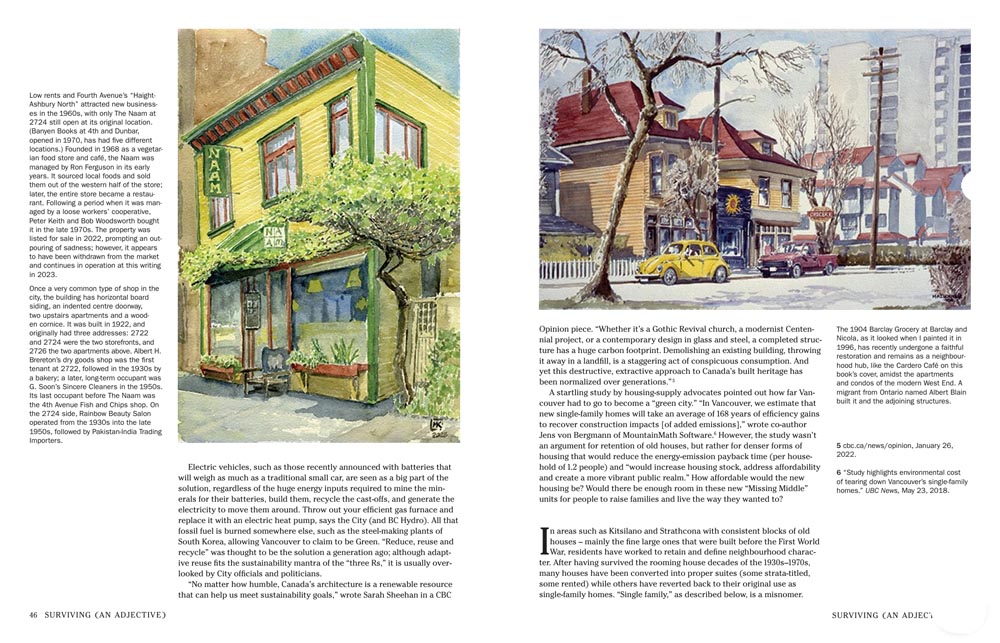

There are new and 25-year-old watercolours of familiar places that have somehow survived the march of progress...

And some images of favourite places that represent the best of Vancouver's neighbourhoods...

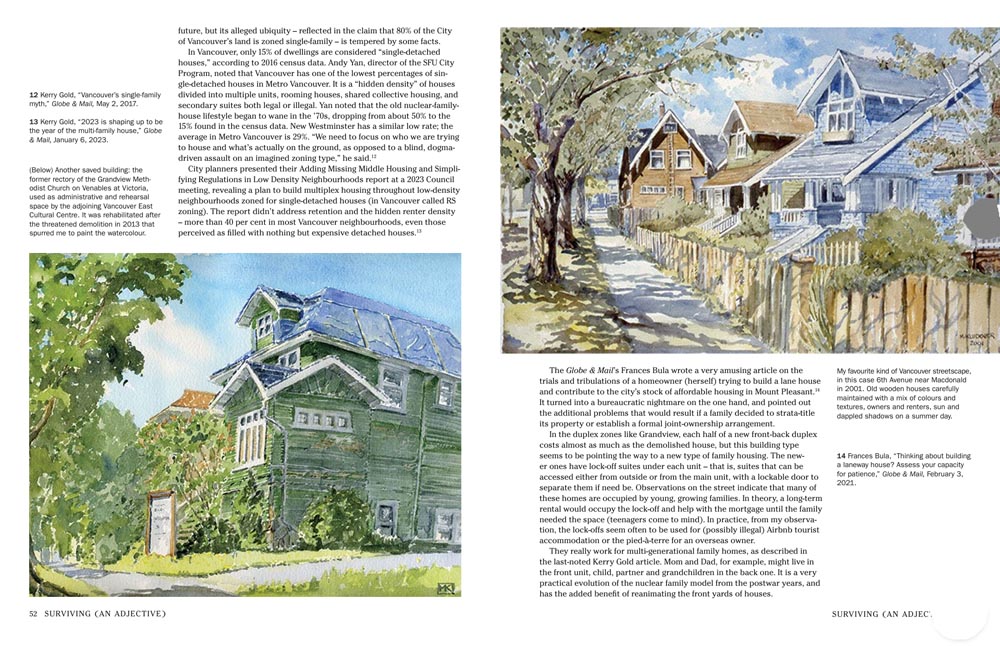

And sections on the beleagured historic sections of the city and how they're trying to survive...

The final section talks about people surviving by leaving: is it working for them or ...?

****

Reviews

CBC interview with Gloria Macarenko.

Published April 11, 2024 in The Tyee

***

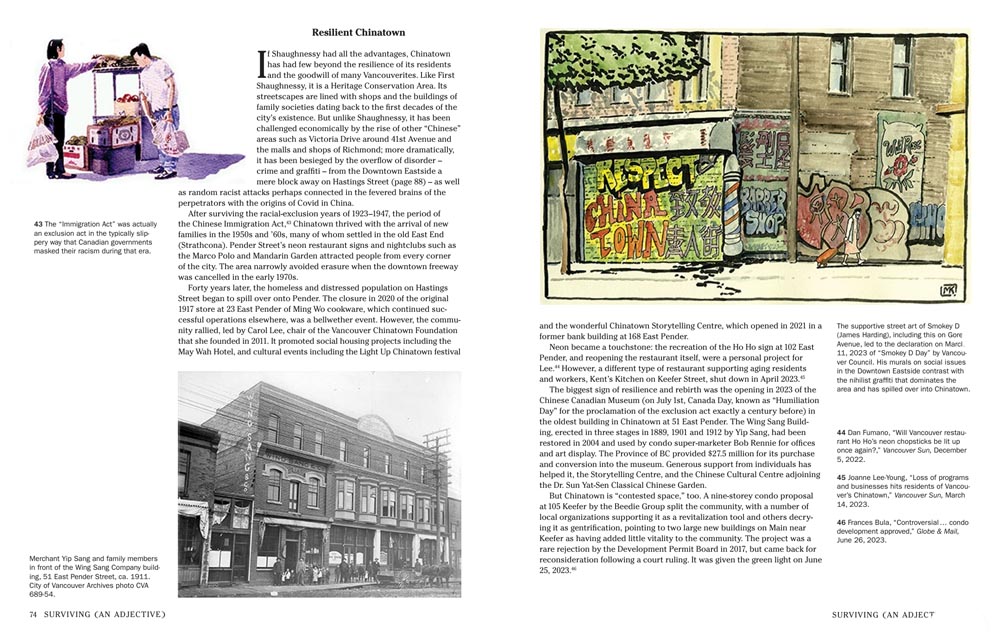

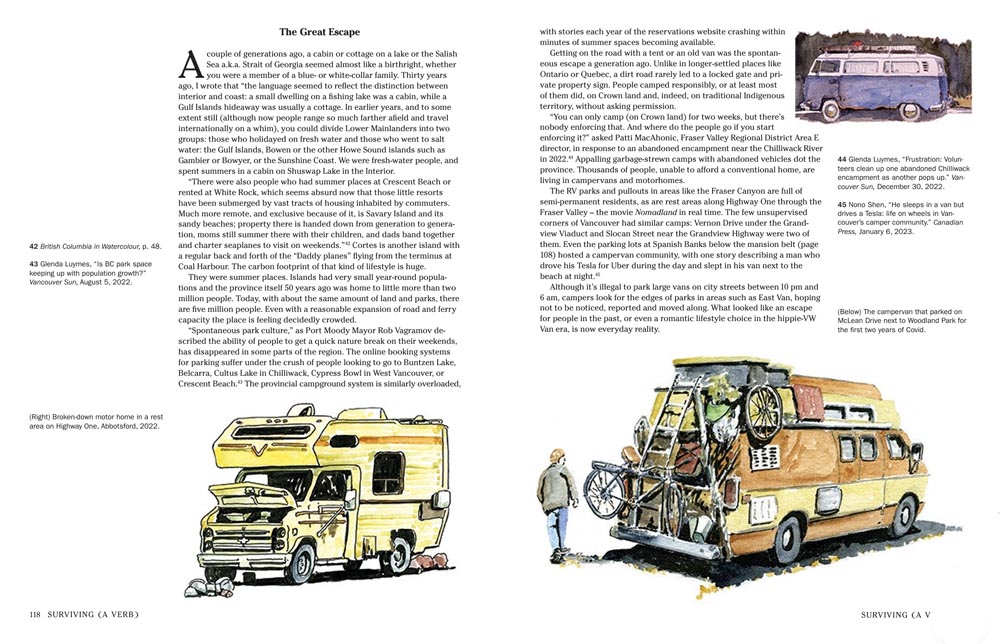

Douglas Todd, April 16, 2024 (a link to the original article)  Vancouver's Sheraton Landmark Hotel, captured in this 2000 watercolour, has been demolished and replaced by luxury condominiums. The grocery store has been reworked as the Cardero Café. (Image is on the front cover of Michael Kluckner's new book, Surviving Vancouver.) SUN What survives of early Vancouver? And how can residents survive contemporary Vancouver? Those are the questions historian and artist Michael Kluckner delves into in his edgy new illustrated book, Surviving Vancouver. Sadly, Chuck Davis, effervescent historian-about-town, died in 2010. Yet we still have Daniel Francis, who recently completed Becoming Vancouver, a chronological history. And Kluckner, who at age 73 has put together at least half a dozen books on Metro Vancouver, and has now written what he calls the “conclusion” to his series. Kluckner’s history books, with their unique addition of watercolours and drawings, started in 1984, with Vancouver The Way It Was. That was followed by Vanishing Vancouver in 1990, which won many awards and resulted in him being characterized as a heritage champion. While Kluckner has always put tenderness into his images, some now more frequently point to trouble. They more often quietly capture residents’ discomfort with this metropolis of 2.5 million people. And Kluckner’s penetrating words expand on his illustrations, probing the big cultural and political themes that have long been threatening the region, which have turned more urgent since the turn of the century. When he focuses on the word “surviving” as a verb, many of the issues he pinpoints revolve around housing unaffordability. It reminds me of writing in 2018 that housing had become the city’s worst emergency since the Second World War. Since then, no one I’m aware of has offered a counter argument. To say the least, Kluckner wouldn’t disagree. Things have sped up fast in this gateway city. In his 2024 book, Kluckner reflects on how his 1996 book, titled Michael Kluckner’s Vancouver, “was a gentle thing, done at a time when the city seemed quite stable and affordable, in a pause between the post-Expo boom and the development frenzy that began soon after the Millennium.” Today, in contrast, he says one of his friends describes his latest book as “acid-tinged.” In it, Kluckner notes the National Bank of Canada calculates it would take a Vancouver person on a median income 28.5 years “to be able to afford a downpayment to buy a house.” Whereas, in Winnipeg or Edmonton, it takes that same individual just 29 months. Kluckner pays close attention to journalists, economists and housing scholars. Citing the latest research, he reminds us how money brought into Canada by “satellite families” — which B.C.’s speculation tax form defines as those who earn most of their income offshore — often goes into housing investment, especially at the high end. And one UBC study found “owners of Greater Vancouver homes with a median value of $3.7 million pay income taxes of just $15,800 — exceedingly low for North American cities.” In a chapter titled “Making Room for the Rich,” he juxtaposes a colourful older Vancouver building with the angularity of The Alberni, one of Vancouver’s new luxury towers for what are now called “ultra-high-net-worth-individuals (UHNWI).” Despite being a watercolour, its cool, discordant sensibility echoes what is happening to this city, which few believe is growing warmer in character.  ‘The Alberni,’ a new luxury apartment tower in downtown Vancouver, by Michael Kluckner, captures the discord of this evolving region. From the book, Surviving Vancouver. SUN Along with the influx of money into Metro Vancouver, Kluckner wonders about the ennui settling in. He quotes several people on the subject, including Kaitlin Fung, who says, “As a lifelong Vancouverite, I often wonder: Why is it so easy to feel alone here?” One national study ranked lonely Vancouver as the “unhappiest city” in the country. It gets Kluckner musing: “Is urban design the cause of social isolation, or is it the Internet and the tenuous camaraderie of social media? Or just the scale of cities, whether it is Vancouver or Surrey?” Although Surviving Vancouver devotes energy to analyzing wealth gaps in the region, it needs to be emphasized Kluckner’s affection for this place keeps bursting through. His book reverberates with beautiful watercolours, historical maps and fetching illustrations, old and new. There are lovely sections on fascinating neighbourhoods, past and present. They include a long essay on Shaughnessy, plus explorations of Chinatown, Hogan’s Alley, Burnaby’s Brentwood and Richmond’s farmland, including its recently banned mega-mansions. Cleverly, to capture the city’s rapid evolution, he inserts some 1990s drawings of Vancouverites doing things they no longer do — like standing in telephone booths and even reading newspapers in public parks (shocking!). He also includes pastoral images of old corner stores, trees and even hotels, like the Sheraton Landmark, that have since been demolished for glistening condo towers. Kluckner has witnessed a lot over the years, and it shows. It raises the question: How has he personally survived the evolution of Vancouver? In part by moving away for 18 years, to a farm in Langley and then Australia. His family returned in 2010 and was able to buy a fixer-upper near Commercial Drive because prices were somewhat deflated after the 2008 financial crisis. Still, he finds all the new money, and the strange politics, discouraging. “I’m very frustrated by our inability to convince the City of Vancouver, and now the province, that adapting existing buildings is a green strategy. So is retaining the character and levels of history that more mature cities than Vancouver have,” he said in an interview. Recent schemes by the City of Vancouver and the B.C. government to upzone almost all the province’s neighbourhoods, without consultation, “are the greatest gift to land speculators and assemblers that’s ever happened,” he said. “It’s like the old definition of stupid. ‘We’ve been upzoning property for years and housing is getting less and less affordable, so what we have to do is upzone even more property to higher levels!’ I thought provincially that I voted for social democrats, not social autocrats.” In regard to his own tolerance for what goes on in this endless construction zone, it reminds him of a conversation he had recently with a young Mexican woman in Mexico City. “She was talking about her city’s problems — obviously huge compared with Vancouver’s — and said: ‘It’s a mess, but I love it.’ That’s the way I feel about Vancouver.” Hundreds of thousands of people know what he’s talking about. *********

Kerry Gold in the Globe & Mail, June 21, 2024: ...historian, artist and author Michael Kluckner delivers an illustrated overview of Vancouver’s evolution from a sleepy but charming port town to “a much harsher, more stratified place” in his new book,Surviving Vancouver. Nobody could write about Vancouver without recognizing the recurring themes of land speculation, soaring prices and displacement. Mr. Kluckner points out in his book that it would take 28.5 years for a Vancouverite on a median income to acquire the down payment on a house, based on National Bank of Canada data. “The money made all over the world and brought here, it doesn’t seem to be starting businesses, it doesn’t seem to be creating good wages for people,” he says in an interview. “That’s where our huge disconnect is.” “And secondly, it’s this planning dogma, that in order to make our city grow, we upzone property. So you have to build 12, 20, 30-storeys here, and all it does is cause land assembly and speculation.” ***

Review in Spacing.ca

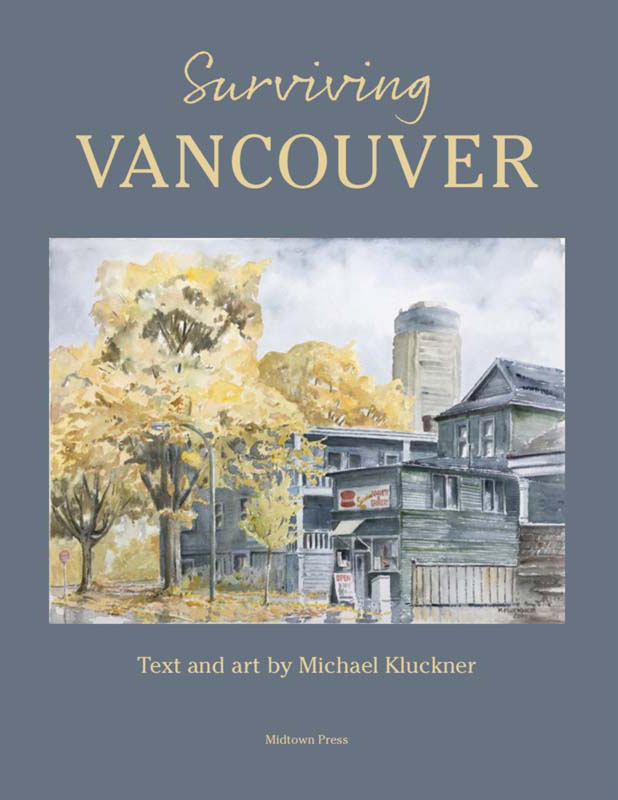

by Sean Ruthen For over three decades now, our understanding of the Lower Mainland in BC has had the benefit of Michael Kluckner’s watercolours. Whether of buildings that have now been demolished or others that have defied the real estate lottery and remain standing, Kluckner’s adept eye has captured the zeitgeist of Vancouver and its environs in a much different way than historians like Hal Kalman and Chuck Davis, or journalists Frances Bula and Kerry Gold. With Kluckner, one is given the impression of this place—the way light plays on the trees that surround an old Craftsman in Kitsilano, for example—and the body of work he has done over the years is astonishing, captured in the many books he’s published since the 1980s. As he notes in the introduction,Surviving Vancouveris in response to three collections of his paintings, but most notably Vancouver the Way it Was(1984) which he released leading up to Expo ’86. To see how much has changed over the years, his art is accompanied by his erudite experience of growing up in Vancouver, especially through the activist spirit of the 1970s. Divided into two parts, the first half of the book looks at the buildings and places that have survived the region’s rampant development over the last three decades, with one casualty depicted on the book’s cover—the Sheraton Landmark Hotel on Robson Street—the demolition of which Kluckner refers to as a climate crime. It is one of many buildings that are now gone from our streetscape, including the old Ridge movie theatre in Kitsilano which is now just a sign on the side of another real estate development. As such, the first half of the book is an up-to-the-moment snapshot of our surreal real estate market, including depictions of tents on the streets alongside articles on empty home taxes and short-term rentals. A lengthy section dedicated to the zoning evolution of housing in Shaughnessy is paralleled by another focusing on Chinatown, both portrayed as positive narratives compared to those of Japantown and Hogan’s Alley, two neighbourhoods that have not survived to our present day. Reflecting on his initial paintings of these places, he never could’ve foreseen their transformation into contested spaces, where soaring real estate values would intersect with truth and reconciliation efforts. Vancouver is now in a turbulent period of repositioning, and Kluckner’s artwork and historical writings serve both at once as a poignant reminder of our recent past while pointing to potential future paths forward. In the second half of the book, Kluckner explores the experience of trying to survive in Vancouver amidst our current real estate climate. A telling sign of the book’s timeline is his mention that the Crab Park encampment remained intact, something that changed in early 2024. He traces its origins to earlier encampments like those in Oppenheimer Park, reaching further back to the era of the Great Depression when unemployed men hopped off boxcars to establish shantytowns near Ballantyne Pier. This section starkly illustrates the great divide between the affluent and the marginalized, juxtaposing the history of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside with portrayals of new multi-tower developments around Oakridge and Brentwood malls. In one of the book’s more whimsical moments, Kluckner riffs on the gesamtkunstwerk of the Vancouver House—a recent addition to the city skyline—with another expression, “schadenfreude,” to describe the debacle when a water main gave way shortly after the building opened, flooding twenty luxury condos. His wit and sense of humour have graced all of his books, including my personal favourite Vanishing Vancouver (2012), in which he provides illustrations of several Vancouver house types, including the notorious Vancouver Special. While he may think of himself as an artist first and an activist second, he describes his meeting with Caroline Adderson when she published Vancouver Vanishes in 2015 as the moment when he realized Vancouver was demolishing thousands of the very houses he had been painting every year, replacing many with empty monster homes built for the real estate speculation industry. And while much of what he recounts here will be familiar to many, there are several gems peppered throughout the book, including the demonstration at Lost Lagoon in 1971—itself a tent city occupation—to protest the plans to build a 15-storey multi-tower commercial development at the doorstep of Stanley Park. While the development never got built, the ensuing violent VPD cracked down on the protesters became known as the Gastown Riots, and has been immortalized by Stan Douglas in a photomural at the new Woodwards development close to where the riot occurred. Surviving Vancouver is a reconciliation with the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh who have stewarded and shared this land we call Vancouver since time immemorial. While this acknowledgment is a start, he notes we still have much work to do, succinctly capturing in his watercolours the struggle of people from all walks of life. He notes how no one had cellphones in those early paintings from the 80s and 90s, something much different than today. Kluckner also updates his visual narratives to include short-term rental folks on city sidewalks with their luggage, along with a tattooed youth on their laptop in a coffee shop. Michael Kluckner continues to be our modern Virgil—guiding us now as he has so many times before. Surviving Vancouver is a blueprint to help us navigate the tumultuous changes affecting our city. We are better for being able to see the world through his eyes, impressing on us a view of the world where we could collectively re-imagine and re-evaluate this place we call Vancouver.  By John Ackermann Posted July 21, 2024 10:44 am. Last Updated July 21, 2024 11:24 am. Michael Kluckner has been writing about Vancouver and its vanishing heritage for 40 years, becoming, in his words, “a harsh critic of the city’s willingness to clearcut itself, the way settler culture did with the forests that stood here in Indigenous times.” He began with Vancouver The Way It Was, his first book-length study of the city and its suburbs. His latest book, Surviving Vancouver, continues that work decades later. Like many of his previous titles, it is both a richly illustrated remembrance of things past and an incisive warning for the future. “We are in danger of losing what was looking in the 1990s to be a kind of a complete city, one with these layers on the landscape, one with a sense of its own history,” he said. Surviving Vancouver is divided into two parts — one looks at the built heritage of the city that has survived – and the other looks at what people will do to survive here. The first part is entitled Surviving (An Adjective) and it looks at the parts of Vancouver that are still with us today. “For example, some of these inner-city areas, the Strathconas, the Mount Pleasants, Kitsilanos, Grandviews, and so on,” Kluckner said. “They have survived largely because individuals have loved the old houses, loved the neighbourhood quality, and they’ve gone and bought up what, in many cases, were rooming houses that were primed for redevelopment, but instead of tearing them down, they’ve fixed them up.” Then there are aspects of the city Kluckner feels are increasingly under threat. “The affordable apartment areas in Vancouver, and particularly along the Broadway Corridor, where they are building at just an immense cost, a subway to create a second downtown.” Kluckner laments the loss of these areas and the resistance to preserving them. “Mature cities have layers of different landscapes that tell stories,” he writes. “The ‘new Vancouver’ is a general infant of little character and architectural merit that is doing little for the poor.” The second half of the book is entitled Surviving (A Verb), and it looks at everything people have done to afford to live here since the Great Depression. “One of the things that I thought was worth doing in the book was doing a review of the 90 years since poor people have been moving to Vancouver,” he said. Other ways of surviving in Vancouver include the ability to draw from “The Bank of Mom and Dad” to afford a down payment on a home. “It just points the way that the inequality in our society is being baked in generation over generation, compared with, say, 50 years ago,” he said. For others, survival means escaping the city into more distant suburbs where they can afford enough space to raise their families. “If your way of surviving means you got to get out of town, then that’s not, to me, a successful city.” He warns the more unaffordable Vancouver becomes, the more it may cede influence to the suburbs, one in particular. “You know Surrey, for all of its problems, that’s where people are going now. And maybe in 20, 30, years, [we’ll] refer to this whole area as Metro Surrey, not Metro Vancouver.” For an increasing number of people, Kluckner says survival also means a van or a motor home is the only shelter they can afford. And for retirees, it means fleeing to the east side of Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands, or the Okanagan — turning what were once BC’s summer places into permanent homes. But for all of Vancouver’s sham, drudgery, and broken dreams there is no place Kluckner would rather be. “I don’t want to be one of the ballcap-wearing retirees over on the east side of Vancouver Island, complaining about how things used to be better,” he said. “I’d rather stay here and work and try to make this city better and make it continue being a lovely place.” And in his own way he has. Surviving Vancouver is published by Midtown Press. By Peter Hay Even if you have never been to Paris, you can still get a feel for the city from the many artists who painted it. Fashions and vehicles have changed since the Impressionists captured them but the buildings and the bustling energy are still recognizable today. The same is true for Dutch cities of the Golden Age or for Canaletto’s Venice of the 18th century. Not so with Vancouver, which has been largely the preoccupation of Michael Kluckner for more than four decades. As an artist, writer, historian, conservationist, and activist, he has depicted the city where he lives through deceptively soft and charming water-colours of shady streetscapes, verdant parks and historic mansions. The titles of his many classic books – Vancouver the Way It Was, Vanishing Vancouver, Vancouver Remembered, etc. – sound nostalgic and even sentimental. Surviving Vancouver is another addition to the work of Vancouver historian and artist Michael Kluckner’s books exploring Vancouver’s liveability and frequently changing landscape. But the text in each book reflects a gradual sense of disquiet and provides critical commentary on what the city has allowed to be done to heritage buildings, obscuring her natural scenery and what Kluckner calls cultural geography. His first book, Vancouver the Way it Was, published in 1984, a couple of years short of the city’s centennial, was a kaleidoscope of historic photographs, maps, descriptions and paintings in colour, resembling old postcards. As the title suggests, it was an illustrated history of the city which seems to have forgotten that it has a history. Surviving Vancouver, published forty years later, is a reckoning with that lost history. The word in the title divides the book into two parts. Surviving as an adjective refers to the buildings and cityscapes that somehow managed to survive the past century of booms and depressions, immigrations, and globalization; whereas surviving as a verb deals with the social divides in a city – and province – where sheer survival is a daily challenge for far too many people. Two small paintings sum up the fight for survival in what Kluckner calls Vancouver’s ‘contested space’. One shows a homeless person in a shapeless heap on the pavement of Georgia Street, right below a Hudson’s Bay window displaying fashionable attires by elegant mannequins. For total realism, Kluckner notes the date and time: 11 am. April 13, 2022. Since then, of course, the Bay itself has closed its doors, the mannequins were first stripped naked and now are gone, but we know that the homeless are still on the pavements in greater numbers than ever. The other painting is from a year later, showing the classical Birks building on the same street with the landmark clock tower, and a homeless tent next to it. “From the tent comes moaning and shouting,” Kluckner writes. “ – a man crying out in a mental health crisis. He can be heard a block away, but there is no one to help. People walk by, it’s normal…” Heading down Georgia towards Stanley Park, barely a mile away, Kluckner depicts how the rich live in high-rise condos like the Alberni Tower looming over the 1910 gable building barely surviving in its shadow. Ever the social chronicler – he is president of the Vancouver Historical Society – Kluckner explains how these monstrous buildings have been reshaping the West End since the 1950s. In a section subtitled “Making Room for the Rich”, he tells of the transformation of Coal Harbour that once provided affordable housing on the water for about 700 workers, until these houseboat colonies gave way to today’s idle yachts owned by the wealthy condo-dwellers in the nearby towers: The Coal Harbour shoreline right to the Stanley Park entrance was once as heavily industrial as any land in Vancouver… Houseboats crowded next to every available piece of shoreline, providing housing for people working nearby… …In the early years of the 20th century the Park Board and Town Planning Commission sought to create a Champs Elysees of grand boulevard for Georgia Street and frame Lost Lagoon with formal pavilion-style buildings. Until the mid-1930s and the successful pitch to create the Lions Gate Bridge across First Narrows, there was no conception of Georgia Street and Stanley Park as a commuter route to the North Shore. In a situation reminiscent of today’s shortages, the wartime shipyard workers of Coal Harbour fought for their housing… Surviving Vancouver partners Michael Kluckner’s observations and artwork in a powerful statement Kluckner then quotes a news article from 1944 defending the houseboat colonies, and goes on to describe the 1971 sit-in by the Youth International Party (the ‘Yippies’) to protest the proposed development of apartment and hotel towers at the entrance to Stanley Park. Along with the text, Kluckner shows the tent city occupied by the protest, an illustration from another recent book, The Rooming House (2022), which captures his own hippie days in a monochrome graphic style. Michael Kluckner’s painting features Nelson Street, looking east toward Burrard in 1986 Surviving Vancouver is a worthy and valuable addition to Michael Kluckner’s considerable oeuvre. It is full of visual delights even when he paints the ugly contrast between Vancouver’s spectacular setting against the dense highrises, or the rusty remains of a departed industrial era. The images are powerful and speak for themselves, but the words add many historical details about bygone characters, how they lived and what they built. There are typical paintings in the familiar Kluckner style, some reproduced from his earlier books, which show old and colourful neighbourhoods like Shaughnessy and Chinatown, and where preservation rules, or at least survives. Kluckner – who founded the Vancouver Heritage Society and served on both the British Columbia and the Canada Heritage boards – conveys a unique feel for the past. Not just buildings and streetscapes that are worth preserving, but also a way of life that is fast vanishing, such as people casually reading newspapers on a city bench instead of bending over their cell phones. This slim volume combines many of Michael Kluckner’s passions for preservation, and also sums up his lifelong preoccupation with Vancouver as a liveable space. Although the blurb on the back cover says that it concludes his study of the city, Vancouver needs his pen, his brush and voice perhaps more than ever. Fortunately, the reader can also turn to his website, michaelkluckner.com, which provides a comprehensive picture of his evolution as an artist and activist, how he came to create his books, where his current thinking and projects stand. May he long survive in the city he so clearly loves. |

Art and text ©Michael Kluckner, 2025