Text & artwork © Michael Kluckner, 2009

Contact me Return to home page

|

|

|

|

|

A The

distinctive

“Okker,” “Strine” or

“Broad Australian” accents of Olde Australia are

more a country thing, so newcomers – likely settled in a city

– will probably not hear them, and even the characteristic

Aussie inflections in cities are now often overlaid with foreign

accents. The most Okker accents on television tend to be the

sportscasters on the evening news, whether private or public networks; when the players, especially the footy ones, are interviewed, the newcomer cries out for subtitles. The

distinctive

“Okker,” “Strine” or

“Broad Australian” accents of Olde Australia are

more a country thing, so newcomers – likely settled in a city

– will probably not hear them, and even the characteristic

Aussie inflections in cities are now often overlaid with foreign

accents. The most Okker accents on television tend to be the

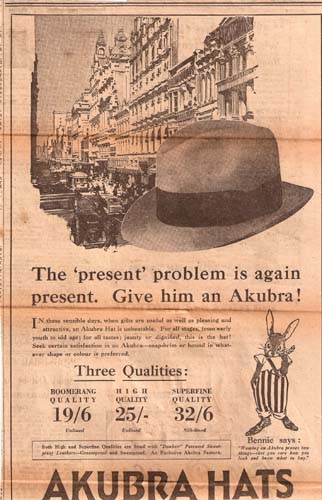

sportscasters on the evening news, whether private or public networks; when the players, especially the footy ones, are interviewed, the newcomer cries out for subtitles.The classic way to learn the basics of a broad Aussie accent is with a copy of “Let Stalk Strine,” published in 1965 and as impossible to understand today as it was then. Alastair Ardoch Morrison, who went by the nom de plume Afferbeck Lauder, was the author. A more recent version of Okker escaped from the bush into the wider world through the TV programs of the “Crocodile Hunter,” the late Steve Irwin. If you want to develop an Australian accent, in order to annoy native speakers or to demonstrate to the overseas rels how well you're adapting, follow these simple rules: -any word with an "a" sound, as in state, pronounce with an "eye" sound, so it sounds like styte; mate becomes mite, station becomes sty-shun. -any word with an "eye" sound, as in right, pronounce with an "oi" sound, so it becomes roit! -never pronounce a final "r" sound. Practise as you drive around in your kah. -practise with your teeth together, quickly repeating the phrase, "you have to talk with your mouth closed so the flies don't get in," pronouncing flies as floys, and you'll hear the beginnings of a proper Australian accent. -mumble -if you're young and female, speak very quickly and use your tongue’s interaction with the roof of your mouth, rather than the movement of your lips, to pronounce your words, which will eliminate most of the consonants. The resulting baby-talk sound will blend you in with your contemporaries, especially if they’ve drunk too many alcopops. -Kiwis have a slightly different accent, mainly noticeable around the pronunciation of short i's. So sex sounds more like six, for example, which doesn't imply group six. Australians speak very quickly compared with, say, Texans, so the issue of comprehension + accent can be a problem. Note the tendency to verb nouns: that is, to make a verb out of a noun. Australians "farewell" friends going overseas, for example, which is not totally weird as every English-speaking country welcomes people. A talk will be auspiced by a club (that is, presented under the auspices of...). It's all about shortening words and phrases, noted below in bottle-o. And also, you have to pay attention if somebody's giving you a phone number! For example, in a phone number 22 is always pronounced "double two," even though it's an additional syllable compared with just saying "two-two." So the country's standard 8-digit phone numbers are not broken into four digits followed by four digits, but instead, for example, 4782 2577 would be pronounced as "fourseveneightdoubletwofivedoubleseven," at break-neck speed. *** I enjoyed your description of Australians speaking through their teeth while speaking. So funny. I must have forgotten because a couple of years ago a friend was telling me that they had enjoyed visiting Australia and how Australians speak through their teeth. They speak like this, she said, clenching her teeth as hard as she could. How interesting, says I... I must have forgotten that characteristic. Anyway, a few months later we went on an Eastern European tour with Trafalgar Tours. We thought people would have been British most likely. Anyway, they were mainly Australians with a handful of Canadians, Americans and British alike. We all got on the bus in the beginning and this Aussie spoke to me and I sat fascinated and couldn't believe my eyes, "she was talking through her teeth". My goodness I thought ... how could I have forgotten that habit.  Akubra: the hat you need to wear to avoid skin cancer while looking like a traditional Aussie. A business that began in Tasmania in 1874, Akubra has been controlled by the same family for more than a century. They are felt hats made from rabbit fur – founder Benjamin Dunkerley’s technical breakthrough was to invent a machine that removed the hair tip from a rabbit pelt so the under-fur could be felted. In a country overrun with rabbits, wearing one of the hats seems almost patriotic. Alcopops: the RTDs -- that is, the "ready to drink" bottles of hard liquor mixed with some variety of sweet (or caffeine-laced) soda pop. Most popular with the young, they are a sort of cocktail with training wheels, disguising the kick of the grog with familiar soft-drink tastes. According to the government, they are responsible for much of the binge-drinking of the wayward young and, as such, were surtaxed federally until early in 2009 when the enabling legislation failed to make it through the Senate. Alice (Springs): the biggest Outback town, the jumping-off point for Uluru, the deserts and mountains of the Northern Territory and the heartlands of desert Aboriginal culture. It is visited by lots of tourists and grey nomads, and most Australians say they hope to get there some day. Once just a dot on the Adelaide-Darwin telegraph line, it soon became the administrative centre for the desert part of the Northern Territory. Its name went into the world consciousness because of Neville Shute’s romantic novel “A Town Like Alice,” published in 1950 (made into a movie in 1956 and a TV miniseries in 1981): “’There’s only one good place for a woman,’ he said. ‘Alice Springs. Alice is a bonza place, oh my word. A girl’s got everything in Alice – two picture houses, shops for everything, fruit, ice-cream, fresh milk, Eddie Maclean’s swimming pool, plenty of girls and young married women in the place and nice houses to live in. Alice is a bonza town,’ he said, ‘but that’s the only one.’” Ironically, none of the novel’s action actually takes place in Alice Springs. Instead, the female protagonist sets out to improve a tiny dot in Queensland’s cattle country so it becomes “a town like Alice.” ANZAC: the Australia-New Zealand Army Corps, whose exploits in the First World War, especially at Gallipoli, helped define the Australian nation and its sense of mateship and individual valour against all odds. Also an excellent bikkie made with golden syrup, oats and coconut, allegedly so named because it could be shipped during WWI from Australia to the soldiers in Palestine or France and arrive months later still edible. Appearance: Are there non-Aboriginal types of people who look unmistakably Aussie? Sunburnt men and women perhaps, from an Anglo-Irish background, who might or might not have an ancestor who arrived in chains? Would you say, “that’s an Australian,” not because of the Drizabone or the elastic-sided boots or the old hat with corks dangling from its rim, but because of the shape of his or her face or body?  The

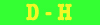

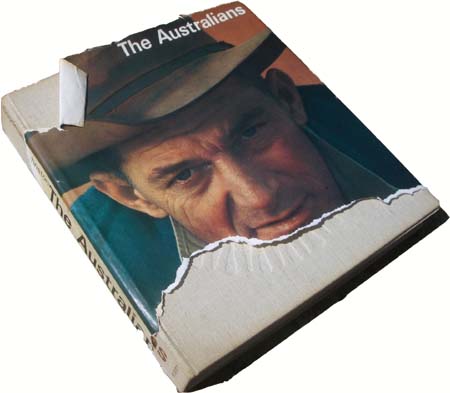

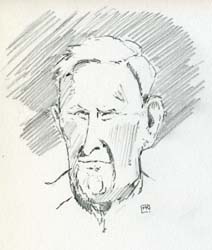

classic caricature

of an Aussie is probably the hatchet-faced man

by painter Albert Tucker, reproduced 40 years ago on the cover of

Donald Horne’s “The Lucky Country.” A

country bloke, eyes narrowed

against the glare, mouth a bit pinched at

the corners, weatherbeaten… Similar images were

the caricatures by Russell Drysdale of lean, mean country men in his

1940s paintings based on the derelict NSW mining towns of Hill End and

Sofala. More recently, actor Paul “Crocodile

Dundee” Hogan and naturalist Steve Irwin gave slightly more

fleshy form to the hawk-faced classic of earlier times. The

classic caricature

of an Aussie is probably the hatchet-faced man

by painter Albert Tucker, reproduced 40 years ago on the cover of

Donald Horne’s “The Lucky Country.” A

country bloke, eyes narrowed

against the glare, mouth a bit pinched at

the corners, weatherbeaten… Similar images were

the caricatures by Russell Drysdale of lean, mean country men in his

1940s paintings based on the derelict NSW mining towns of Hill End and

Sofala. More recently, actor Paul “Crocodile

Dundee” Hogan and naturalist Steve Irwin gave slightly more

fleshy form to the hawk-faced classic of earlier times.Features of the classic Australian male face: -Leanness -eyes squinting against the bright sun -the size and shape of the nose, which tends to be long yet narrow -the size of the ears. Look for large, long ears which may stand out like handles on a trophy -mouths tend to be thin-lipped and small -eyebrows, reflecting English ancestry, might be wildly luxuriant like tangles of barbed wire. -animation -- a classic Aussie face has a twinkle to it, from the eyes and the corner of the mouth, reflecting an awareness of the general absurdity of life in such a hot, inhospitable place. They don’t tend to look beaten-down and gloomy like Poms or Canadians.  The current leader of the

federal Opposition, Tony Abbott, illustrates the above characteristics

except for the eyebrows (and arguably, although this might be construed

as a political statement, the animation), and thus could be subliminally

attractive to voters.

One of the first of the iconic Aussie faces in popular culture, an anonymous stockman, by photographer Robert Goodman. The Australians, written by recently returned expatriate George Johnston and published by Goodman in 1965, was the first of the coffee-table books that attempted to create a sense of the country for a mass audience. It was followed by an avalanche of similar books, most notably the photo-essay A Day in the Life of Australia, published in 1983, which spawned an international series of “day in the life” books.    Characteristic

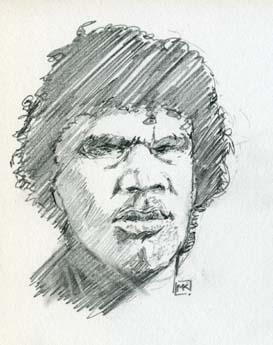

Aussie faces, perhaps?

Features

of the classic Aussie

female are harder to list, but: Features

of the classic Aussie

female are harder to list, but:-as they get older, Australian women have to fight really hard to counter the withering sun and dry hard air, so they tend to go a bit hatchet-faced like the men. -A particular humorous cast to the mouth and a wry, slightly lop-sided smile can often be detected, seeming to reflect the irony of their situation. Like, “are these all the available men?” The classic comment came from an anonymous woman in Mount Isa, the remote, male-dominated mining town in Queensland, when she heard the mayor’s suggestion in 2008 that unattractive women seeking partners could do well to move there: “the odds are good,” she said, “but the goods are odd.” -Young women tend to wear their hair long compared with women in North America or Europe. Do Australians still have the classic lean faces of an earlier era? A 2006 article by Deborah Goodman in the Sydney Morning Herald described the “Facing Australia” photographic project and how the typical Aussie face now had better skin and teeth and bigger mouths than a century ago: “At the most basic level, Australian faces have got fatter with the years. Improved dental care has made a crumpled countenance less common. And eventually, as the message about skin cancer takes hold, facial appearances will become less sun-ravaged than now. “The artist Dr Martyn Jolly says portrayals of the Australian body, rather than the visage, dominated visual culture in the first half of the 20th century with a recognisable ‘face of Australia’ only emerging during the 1960s. This metaphor for a nation was ‘the frank, weather-beaten, blue-eyed man gazing into the sun with a squint,’ says Jolly, of the Australian National University's School of Art. “The iconic Paul Hogan look-alike always was a myth, despite still being used in government advertisements and to give a face to faceless corporations…”   What about body shape? Journalist Greg Callaghan wrote recently that if you were strolling down a typical city street in the 1920s, you’d “be struck by the basic sameness in the bodies making up the crowd. The men, wiry and lithe under their baggy suits and hats; the women trim and taut, even into their 40s and 50s….” (Weekend Australian magazine, April 5-6, 2008, p. 14)  Today,

the fit, lean body of athletic young

Australians has to cope

with the onslaughts of a sedentary culture, processed food and

increased car usage. Lifestyles have changed to adapt to a more

crowded, expensive world: people who live in leafy suburbs such as

those on the upper North Shore of Sydney talk about the numbers of

tennis courts that have disappeared in the past couple of generations

as side yards were sold off and properties infilled. In film and TV

depicting an earlier Australia, such as “Poor Man’s

Orange” and “Careful He Might Hear You,”

working-class children play cricket on the inner-city streets, spaces

unavailable today as every available square metre is occupied by cars.

Fewer people work at manual labour, like agriculture, and those that do

have more power-assisted tools than ever. The result? Australian women

are 12 kg heavier and 2 cm taller than they were a century ago, men 13

kg and 4 cm. Today,

the fit, lean body of athletic young

Australians has to cope

with the onslaughts of a sedentary culture, processed food and

increased car usage. Lifestyles have changed to adapt to a more

crowded, expensive world: people who live in leafy suburbs such as

those on the upper North Shore of Sydney talk about the numbers of

tennis courts that have disappeared in the past couple of generations

as side yards were sold off and properties infilled. In film and TV

depicting an earlier Australia, such as “Poor Man’s

Orange” and “Careful He Might Hear You,”

working-class children play cricket on the inner-city streets, spaces

unavailable today as every available square metre is occupied by cars.

Fewer people work at manual labour, like agriculture, and those that do

have more power-assisted tools than ever. The result? Australian women

are 12 kg heavier and 2 cm taller than they were a century ago, men 13

kg and 4 cm.Arvo: the portion of the day between lunch and dinner. "I missed several business meetings until I realised what people were talking about." – Sandra, who immigrated to Australia in 1998. Ashes: a) what's left of your home and possessions if you built too far into the bush. b) the seminal cricket series between the self-described underdog, battling Aussies (who usually win) and the Poms. A biennial restaging of the Declaration of Independence/Revolutionary War that never happened here but you sometimes wish had, so cricket could be “just a game.” Attitude: Australians have one, no question. The average Aussie, male or female, in the average conversation is funnier, quicker with a quip, faster with self-deprecating humour than you’ll likely find anywhere else in the world. But they’re very direct and will anger just as quickly, so you’re not likely to get just a shrug and a “have a good day…” if you tell somebody to hurry up or get out of the way or if you sneer at their footy team. Friendly yet assertive-bordering-on-aggressive, that’s your typical Aussie – like Americans, but not as heavily armed. “She’ll be right” used to describe perfectly the Aussie attitude to everything and to a diminishing extent still does. Translated, it meant “it’ll do” and reflected the “marvellous, bed-rock indifference” that D.H. Lawrence noted during his brief sojourn in Thirroul, south of Sydney, in 1922. “Everything is happy-go-lucky, and one couldn’t fret about anything if one tried. One just doesn’t care. And they are all like that.” The expression “no worries” is the successor, but can sound less convincing now because Australia has become a much more acquisitive consumer society, with the Battlers having a difficult time keeping up with their fellow Joneses. The Fair Go, a bedrock of the social mountain peak, has a few seismic cracks running through it. Twenty-five years ago the average person had a simpler lifestyle, and an observer from overseas couldn’t help but see the happy balance between the expectations and achievements of the average family. “In North America,” Christine once told me, “when workers go on strike it’s for higher wages; in Australia it’s for more holidays.” After Christmas, for example, the country effectively shut down. Trying to find a head of lettuce or a tank of petrol was almost impossible for about a week. And January was a sort of mass month’s-holiday – the only parallel being the way urban France empties into the countryside in August. Nowadays, the demise of the long summer holiday at the beach is noted every year by the newspapers just after the reports of the huge Boxing Day lineups at the department and chain stores. For better or worse, Australia is now more like the USA than it used to be. From Glenis in Florida: Australians were quick to apply labels to people when I was growing up. I was known as a PB (short for pommy bastard). But an Australian told me that labelling has died away to a certain extent. One label, I recall, was very offensive: Dago applied to Italians and Greeks. [And yet, one of the very successful trucking companies in the Sydney area is called Dago Removals– MK]. |

|

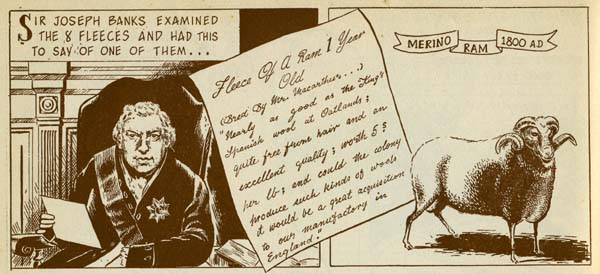

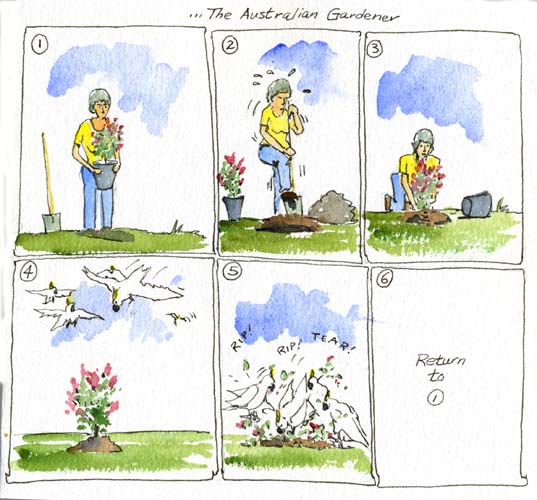

B BYO: As a newcomer, rejoice in the fact that you can take your own wine (sometimes beer, too) to most restaurants and drink it while paying a corkage charge, which could be anywhere from zero to $4 a person. It’s a great system in that you don’t pay a surcharge for the restaurant’s storage and inventory and you can bring multiple bottles, say of white and red, to match individuals’ tastes. It ties in with the servers’ desire to do the minimum possible (see Service), which in the case of wine is a good thing because the server is not constantly hovering, topping up the glasses and trying to sell you another bottle. Banks: a) the fiercely independent free-enterprise institutions that raise mortgage rates in lock-step and have near identical credit-card and savings account rates and would be happy not to have to mail account statements to their customers or do much of anything. You’ll feel right at home with them, regardless of what country you hail from.  Unknown

artist, from The Story of Australian Wool, part of the

Pictorial Social Studies Program, Australian Visual Education, c. 1960.

b) the English botanist on Captain Cook's Endeavour voyage of the southern Pacific Ocean from 1768-1771. Significant as the namesake of many Australian plants, especially the banksia. He made two misjudgements vis-à-vis Australia: firstly, he advised that Botany Bay would be an ideal spot to establish the penal colony in 1778, as he said it had adequate water, building materials and good soil for agricultural; after inspecting it and finding it hopeless, Governor Arthur Phillip, in command of the First Fleet, explored north along the coast, quickly finding the entry into Sydney harbour and establishing the colony there. Secondly, he initially believed that merino sheep would not do nearly as well in Australia as in England. Barbie: a) the doll that is part of the conspiracy to Americanise your daughter, part of “the juggernaut of hot dogs and ice-cream, hamburgers and barbecues, Coca-Cola and Levis, disc-jockeys and TV commercials” writer George Johnston had already noted in 1965. b) the quintessential summertime ritual in the back yard of the quarter-acre block, the only time when men take control at home other than when they're watching TV and insist on holding the channel-changer. In the tourism-promoting TV ads by Paul "Crocodile Dundee" Hogan in the early 1980s, the barbie had a starring role; they painted such a golden, friendly picture of the country that, well, who could not have wanted to immigrate? As evidence of today's advanced barbie culture, most cookers have both a solid plate and a grill of open metal bars above the fire, plus covers, lights, work surfaces and multi-speaker stereos with video screens (okay, not the last one). In the suburban back yards of a generation ago, before the ownership of a $1,500 barbecue became mandatory and air-quality rules came into place, people built a fire of sticks and leaves – the detritus gathered up around the property from beneath every gum tree – between two piles of bricks and cooked their food on a sheet of steel laid over them. And fought sausage-stealing kookaburras bare-handed! A time when men were men and women were grateful, the livin’ was easy, roos were jumpin’ and the wattle was high. Barracking: not your living arrangements if you join the army and get posted to Afghanistan, but what you’re doing when you cheer on your favorite team. Bashed: to be punched out, beaten up.  Battlers: the most stressed-out and economically challenged of employed Aussies, who live in the “mortgage belt,” have to drive long distances to work, to take their children to school, etc., and to shop, where they juggle their credit cards the way previous generations juggled tennis balls. A bribable subset of the electorate whose suburbs are often swing ridings. Beer: a rental product most popular on hot days; a way to convert Australia's chronic water crisis into a worse one. Once upon a time, beer was the national swill, wine was “European” and not many people drank hard liquor. Today, alcopops are hugely popular, especially with hoons and other youth. In the national legend, beer and pubs go together like Vegemite and morning toast. Australia has the fourth-highest consumption rate of beer in the world, but “new Australian government statistics released in February [2003] show that the country's alcohol consumption is at its lowest level since the 1960s. Wine consumption per capita has quadrupled over the past 40 years, pushing beer consumption to its lowest level since 1961, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare said in its latest report. In the 2001 survey, Australia was ranked 15th on the list of overall alcohol consumption, with 9.8 liters consumed for each person aged over 15 years, down from 13 liters 20 years ago.” – source Beetroot: what North Americans call beets, except the word has fallen into disuse as many people identify them with turnips and other winter-survival fare and won't eat them anymore. But Australia has perfected the pickled beet – the beetroot most people refer to. It is delicious and a patriotic additive to every hamburger at every barbie. In the old days, every milk bar's hamburger had beetroot on it. The international chains, such as McDonald's and Hungry Jack's, are further globalising Australia by not offering any beetroot at all. From Glenis in Florida: Those gorgeous Australian hamburgers couldn't possibly be the same without beetroot. Incidentally, it is only the U.S. (and Canada because of its neighbour's overpowering influence) where the veg is called beets. It is pretty well known as beetroot in Britain, South Africa etc. Bikies: what Americans call bikers – the large, heavy, tattooed, Harley-riding gang members. Somehow the idea of calling someone like that an "-ey" anything seems like an invitation to be bashed. In a similar vein, truckers are called truckies in Australia. Bikkie: a cookie, but can also be a savoury biscuit, for example a cheese bikkie. Biro: a brand of ballpoint pen that became a generic, like Esky, for Australians. Biros are used by Poms, too. The writing instrument used by Lord Biro, the great English poet. Bitumen: blacktop, pavement, asphalt. A bitumen road is a “sealed road.”  Bloke: an ordinary guy, which is both positive and negative. Blokiness is reflected in the enduring positive aspects of Aussie culture, including mateship and an easy-going "she'll be right" attitude, but also can be seen in the behaviour of the chauvinistic, conservative leftovers from the past, most of whom have become members of parliament or the senate. In the Kimberley in the 1950s, a worker on a cattle station described to traveller Bernd Lohse what it meant to be a bloke, “what every Australian longs for if he's a real man. As many steaks as you want, enough beer in the icebox, good pals around you, and no chattering women for a month perhaps. In our free time we hunt for kangaroos or we fish.'" Blue: a multi-purpose Australian word 1) the colour of the sky, usually 2) a stoush 3) a common nickname for anyone with red hair 4) as in "true blue" – loyal or genuine, a "true blue Aussie" Blundstones: the most recognisable brand of elastic-sided boots, the de rigueur lowest item of the wardrobe that has migrated from the dusty Outback into the groomed, paved cities. Elastic-sided boots are as much a part of a bloke’s wardrobe as a Chesty Bond wifebeater and a mobile phone. However, like Bonds products, they haven’t been made in Australia since the company closed its Tasmanian factory early in 2007 and moved production overseas.  Bondi: the most famous Australian beach, in Sydney's Eastern Suburbs. It is Ground Zero for Australia's beach culture that has been developing since the 1930s, immortalised then in the photographs of Max Dupain.  From Glenis in Florida: I was

watching a programme on the "top 21 sexiest beaches in the world."

Bondi came 6th (Ipanema 1st with South Beach runner up). One thing that

caught my attention in the programme was the description of the

bikini. It was referred to as dental floss bikini because the

strings are so thin. The dental floss variety makes the

Australian bikini of my day very modest even though we had beach

inspectors measuring the sides of the bikini to make sure that it met

the beach standards.

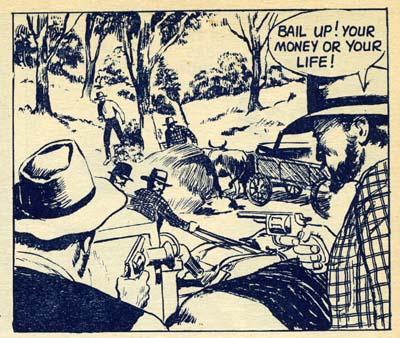

Boomers: kangaroos, traditionally. Now more likely to refer to baby-boomers, the mass of mainly urban post-war children whose impending retirement is causing a crisis in the health-care and super industries and prompting the government to increase its immigration quotas. Bottle-o: a liquor shop. The -oh or -o suffix defines a profession – fisho, rabbitoh – as well as being a catch-all word-shortener for words like registration, which becomes rego. However, as breakfast becomes brekkie and biscuit becomes bikkie, don’t go looking for a hard and fast rule.  Bowls: a game mostly played by the aged, which newcomers usually aren't or they wouldn't have been let into the country. Like cricket, it is only moderately exciting to the mind and pulse, so there is no need to take out additional health insurance before playing or watching. Bowls has the additional advantage of being quite a brief game, leaving adequate time for tea and/or drinks afterwards. Many towns and suburbs have bowls clubs that offer full service like the RSLs and leagues clubs. Broken Hill: the iconic western New South Wales mining town where you'll probably never go until you become a grey nomad. It continues in the urban language due to the company BHP [Broken Hill Proprietary]-Billiton, one of the mining giants upon whose fortunes the Australian economy rides. Butter Menthols: the best way to soothe a sore throat after yelling at an Australian government department or big business, all of which are accessible only via call centres. "Your call is very important to us – please stay on the line and the first available operator will be with you in ... three ... hours ..." Bungy: the straps called bungy cords in North America are, in a rare failure of the Australian verbal imagination, called "tie-downs." Everything else is named so colourfully, so why tie-downs? However, bungy-jumping happens here, under that name, for the young and invulnerable. Do not confuse it with budgie-jumping, the most popular sport in the Cat Olympics held every four years since its successful introduction in Sydney in 2000. From Sal in Adelaide: "We call them ocky straps (Maybe short for octopus, I'm not sure)." Bush: a) former Prime Minister John Howard's best mate. b) the landscape in its natural state, what in other countries would be described as the forest, the woods, the boondocks, the boonies, the toolies or the sticks. It also refers to the poor, rural fragment of modern Australia: that is, everything that isn't part of the metropolitan sprawl. "The bush" as a political force has shrunk considerably due to the collapse of rural employment and the migration of country people, especially the young, into the big cities. This is one of the changes in Australian society that newcomers from North America and Europe will identify with right away and, like there, it’s been a slow train comin’. “Newer times are upon us; there are television towers in the landscape and changing tastes among the country people. The dated little enterprises, those movable feasts of a continent’s hinterland, are being forced further and further into the back country. The times are intruding on, and will someday obliterate, many of the slow and gentle rhythms of country living, where townspeople envy local sheep owners for imagined wealth, where curtains twitch and gossip has an easy gait, reputation can ride precariously on the thin edge of prejudice, and like the biblical sparrow, no local girl will fall unheeded, where the whole district will give up its week-ends to harvest a sick farmer’s crop or build a scout hall for the local kids…” George Johnston, The Australians, 1965. Bush fire: the great rejuvenator of the Australian ecosystem. Unlike forest fires elsewhere in the world, bush fires don't usually kill the trees or underbrush. A year or so after a typical fire and the trees have leafed out again, leaving as the only evidence their blackened trunks. Recently the fires have been becoming much more lethal due to the "tree-changers" – exurbanites – moving into the bush, especially north of Melbourne, leading to situations like the catastrophe of 2009. Bushranger: not the helpful national park employee but a rural outlaw from Australia's folkloric past. The equivalent of the gunslinger of the American Wild West. Ned Kelly is the best-known of them.  Unknown

artist, from the Romance of Gold in Australia, part of the

Pictorial Social Studies Program, Australian Visual Education, c. 1960.

An aficionado of the Aussie touring experience could believe that the main activity of bushrangers was visiting small-town pubs. There’s a sign on the pub at Jerilderie, Victoria saying, “Ned Kelly stayed for three days – why don’t you?” In his definitive history, “The Australian Pub,” J.M. Freeland, wrote that “every self-respecting country pub has a bushranger story – it was either held up, escaped from, holed-up in, slept at, or last-standed on, preferably with a side-play of dead troopers or terrified guests, by the most dangerous desperado ever to cock a snook at Her Majesty’s Government. If all the bushrangers who ever were had spent all their time dashing in and out of pubs they could never have achieved a tenth of the things credited to them.”  Bush

poet using early-model laptop.....

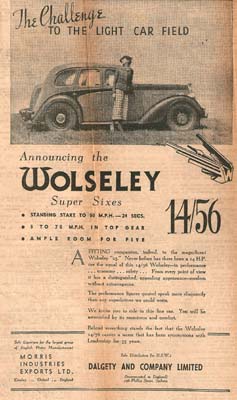

Bush poetry: Banjo Patterson, Henry Lawson et al wrote ballads that defined the colonial era, including The Man from Snowy River, Clancy of the Overflow and The Wild Colonial Boy. The ability to recite them was once a required part of the typical school curriculum during the era when urban Australia sought its moorings in the traditions of the countryside (and when memorisation was considered to be a good use of schoolchildren’s brain power). The only parallel that comes to mind from elsewhere is Robert Service’s Songs of a Sourdough, verses from the Klondike gold rush of a century ago. The tradition of writing verse, some of it satirical, political and wildly funny, continues to this day, with bush poets often featured entertainment at country fairs, as cowboy poets are at American rodeos. C Cactus: from Sandra – means something is broken, not working or screwed up ... as in "my car is cactus." This then would be an updated version of crook. It may be an adaptation of an American term, or a variation on "cacked" or "carked." Caravanistan: the home where the grey nomads roam.   1936

advertisements from Sydney newspapers

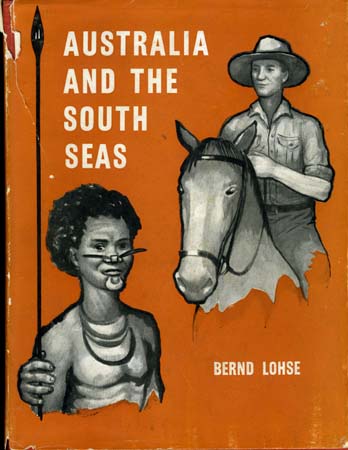

Cars: once upon a time there were just imported cars, manufactured in England, supplemented by American ones assembled in Australia with their steering wheels on the wrong side. A true car industry began in 1948 when Holden, a division of the American giant General Motors, began to manufacture in Victoria a sedan usually called the FX (officially the 48-215). Evolving into the FJ and developing iconic off-shoots such as the ute, Holden cars gave a distinctly Australian look to the roadscape of the 1950s. “Football, meat pies, kangaroos and Holden cars” mirrored the baseball and hotdogs of the Chevy ads of that period in the USA. Along came Ford, building a local version of the Falcon – its American small car of the 1960s– and creating its own utes. Holden’s FJ evolved into the Special, then the Kingswood and finally in the 1970s the Commodore. The Falcon just continued to evolve so that, today, Falcons and Commodores have a real design similarity and compete with each other both for sales and on the racetrack in the “V8 Supercar series,” a favorite of the rev-heads. There were other models along the way from both Holden and Ford, but the Commodore vs. Falcon rivalry is the venerable one. In the globalised auto market of today, Australia’s roadscape doesn’t look much different from anybody else’s, dominated as it is by imported styles from Japan, France and Germany. A generation ago it really did look distinctive, though. Besides its Holdens and Falcons, it was English with its Austins and Morris Minors and Minis, some of which were Mini Mokes – beach cars with a roof structure to hold surfboards – and its MGs and TR3s and Sprites. And there were also curious small Datsuns, tiny Daewoo vans and other odd little vehicles that otherwise never made it out of Asia. A common sight then, as now, was minuscule Daihatsu dump trucks, their narrow cabs stuffed with two or three beefy workers in Chesty Bond singlets with suntanned, hairy arms – reminiscent of Italian “piaggio” 3-wheeled trucks and their occupants. For someone from the USA, even the “big” Holdens and Fords seemed curiously small and narrow (indeed, the original FX project had begun on American drawing boards but had been rejected for the market there as it was considered too small for a family sedan). And their designs were just a bit different from well-known models like the American Falcon, as if they’d been parked too close to a nuclear reactor. To overseas viewers that slight difference gave the movie Mad Max, about road warriors on the mythic Aussie bitumen, another jolt of otherworldliness in addition to its menacingly feral outlaws and post-apocalyptic Outback landscape. There were other distinctively Australian adaptations a generation ago. Many cars, whether VW Beetles or Morris Minors or Holden Specials, were fitted with sunshades like the peaks of ball caps, and had perspex wind deflectors attached to their side window frames to make driving with the window rolled down more comfortable. These things have all but disappeared. Why? Glass is tinted now and air-conditioning is almost universal. As an Aussie taxpayer, you will be subsidizing the Australian auto industry, which has fallen on lean times. Fewer people are interested in the large Commodores and Falcons that the factories have been building, their market share having dropped to about 20 percent. Perhaps, once upon a time in the future, there will just be imported cars again?  Chesty Bond: the essential workingman's cotton singlet, aka "wifebeater," usually indigo blue in colour when new and clean, with deep armholes displaying the maximum amount of tanned beef. A uniform once as universal as the "bleu de travail" of the French labourers, although it seems now the trend for Aussie workers is to wear polyester Fluoros instead. Chesty Bond was a cartoon superhero created by Syd Miller in 1938 to promote the Bond company’s underwear line. Chesty’s singlet was always white, though. The parent company of Bond's was much in the news in early 2009 for closing Australian factories and sending the jobs to China. Chook: one of the Australian food groups. It is divided into two basic categories: a) ones that walk around. The home-grown traditional one is the Australorp, a large, bulky chicken that, in a cruel joke, has heat-absorbing black feathers. It is also known as the Black Orpington. Once upon a time kept for egg-laying, they picturesquely adorned the barnyards of farms large and small. The commercial egg of modern supermarkets comes from cage-layer operations employing modern hybrid chickens like Hy-Lines and ISA Browns – the same as elsewhere in the world. b) ones that ride around on a spit in a rotisserie at the "Charcoal Chook" shops all across the country. Using a secret recipe known only to the thousands of chook-shop operators, chooks are stuffed with bread and intensely flavoured with salt, herbs and fat and roasted to a golden-brown exquisite state. A "chook raffle" is about as cheap as a prize can get, and a luckless individual "couldn't win a chook raffle."  Christmas: a summertime holiday with a main meal usually featuring prawns, salad, beer, chardonnay and, perhaps (for newcomers from the northern hemisphere), an acute sense of longing for cold weather and distant friends. At traditional Australian Christmas dinners a generation or more ago, housewives tried to stay with the English standard of stuffed goose with all the trimmings followed by hot plum pudding with brandy sauce, regardless of the sweltering weather; when combined with the formality of clothing of the time, the pile of heavy food stunned families into such a torpor that it's a wonder the holiday wasn't scrapped altogether. But in more recent years Christmas has become the day for cold seafood, especially prawns, creating line-ups at the fish markets equal to the traditional ones at the department and electronics stores. Small plantation-grown conifers are now available for sale and compete with cheap artificial trees; the era of using a branch of a she-oak or other native tree on which to hang the baubles and tinsel has pretty much disappeared. The southern Christmas entered the northern imagination through Rolf Harris's "Six White Boomers" – the "snow-white boomers / Racing Santa Claus through the blazing sun … on his Australian run” – in the 1960s. Best not to try it as a sing-along with your Aussie friends, let alone any of his other early tunes such as “Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport.” But help is at hand for disoriented, cold-weather-missing newcomers! Tom, of the “Christmas in Australia” website, offers all kinds of advice and includes lyrics for an Australian Jingle Bells: Dashing through the bush, In a rusty Holden Ute, Kicking up the dust, Esky in the boot, Kelpie by my side, Singing Christmas songs, It's Summer time and I am in My singlet, shorts and thongs… Class: part of the now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t reality of Australian life. Describing an earlier Australia, architectural historian John Maxwell Freeland wrote: “In the 1930s when people were grateful to hold any kind of a job a country girl was prepared to put up with a shrewish mistress, unreasonable demands, a 14-hour working day with only a half-day a week to herself, and do any work from making beds to gardening, from cooking to washing babies or laundry for her bed and board and 15 shillings a week. All upper-class and most middle-class homes had domestics. Those who did not at least had a laundress and a charwoman to do the heaviest of the housework for two shillings and sixpence a half-day. Only the working-class housewife had to do all her own work. After 1946, domestics were a vanished race.” (p. 269) The large number of Australians still sporting British knighthoods (none of which have been awarded since 1986, mind), and the large number of hyphenated, rather English names indicate perhaps that some Australians are “more equal than others,” in the old phrase. How do Australians distinguish themselves from each other, amidst what writer George Johnston described as “the curious and disquieting sameness that pervades all Australian cities”? He provided a clue in 1965 that has a ghostly resonance today. “Australians say that when a stranger arrives in Perth the first question asked of him is, ‘Where do you come from?’ In Adelaide it is, ‘What church do you belong to?’ In Melbourne, ‘What school were you at?’ In Sydney, ‘How much money do you have? And in Brisbane, ‘Come and have a beer.’” (p. 71) Claytons: From Sandra – means "fake", imitation or poor quality ... apparently taken from the brand name (Clayton's) of a non-alcoholic drink that was packaged to look like whiskey? I had a guy use the term with me a few weeks ago when I got a quote for some building work and the guy referred to the other company's quote as "Clayton's quote" (see Wikipedia for full background). Cleanskin: an unbranded wine, usually in a bottle with a label stating something like "South Australian Shiraz," and sold at a price similar to that of the "gag in a bag" cardboard casks. Originally the term cleanskin referred to unbranded livestock; politicians without any party affiliation or strong ideology, or who are free from scandal, are also called cleanskins. Coffee: don't expect to find brewed or filter coffee unless you patronise Starbucks or one of the American fast-food chains (but Starbucks, which has taken North America by storm, expanded too fast in Australia: 61 of 84 Australian outlets closed in August, 2008, a rare setback for the galloping Americanisation of Oz).  Aussie coffees are made with espresso beans like European coffees, but have their own names (with the exception of the universal cappuccino): -a Short Black is like the French “petit café.” A jolt of caffeine that comes without the glass of water that Greeks serve. -Long Black is what Europeans call an Americano. It has more water in it than a Short Black and will only take part of the skin off the roof of your mouth. You will probably be looked at as a weirdo if you ask for a Long Black with a little milk or cream in it. Order a flat white instead. -Flat White is a latte. Sometimes in the cities you will find both a flat white and a latte on the same coffee menu; demonstrate your patriotism or internationalism by ordering accordingly, and regardless you'll get the same coffee.  Most city coffee shops are designed so they can be cleaned with a fire hose. No absorbent surfaces muffle the sounds of clattering cups, hissing steam pipes and the pop music that fills in the remaining few audible frequencies. Generally it is quieter outside at a kerbside table next to the idling diesel bus. Coffee shops do as well as tea rooms. Both types thrive as “morning tea” and “afternoon tea” are very much a part of the daily ritual, whether people work or not. A piece of cake or a “slice” is the standard accompaniment. Foreign snacks like biscotti make gradual inroads. Cocky: the raucous, comical cockatoo which has never seen a garden it didn't want to destroy. Also sometimes used as an abbreviation for cockroaches, which will share Australia with the ants, the flies and the dust after the apocalypse (which occurred in Neville Shute’s novel “On the Beach,” appropriately set in Melbourne). And the use of the word doesn’t stop there: a boss cocky (or cockie) is the foreman you might get if you arrive in the country with few skills; according to the dictionary, a “cocky” is/was a farmer.  Convict: usually a noun. Early travel writers and high-quality Poms remarked on the "taint" or "stain" on NSW, Queensland and Tasmania, long after the convict-transportation era had ended, while convict-free Victoria and South Australia reveled in their supposed higher-class origins. Twenty years ago, around the time of the Bicentennial celebrations, there arose a tremendous interest in ferreting out one’s convict ancestors and an ensuing status – a splendid reverse-snobbery – in being able to prove that one’s forbears arrived in chains. It’s only natural – who could now believe that the English social system that created so many criminals was in any way just? One of Australia’s notable expats, the art critic Robert Hughes, wrote the definitive book on the transportation era in 1987, just in time for the Bicentennial. Entitled “The Fatal Shore,” it left no doubt that the Poms were an evil bunch and, to a disinterested reader with no axe to grind, rhetorically went overboard more often than rebellious convicts did.  He-men jogging in their cossies, Bondi Beach Cossie (pronounced "cozzie"): what you wear when you go to the beach. Among the types of cossies there is the "budgie smuggler" formerly known as the Speedo – the historic fig leaf on Australia’s male swimmers – board shorts for surfers, bikinis for beach babes and every size, shape and colour in between.   Country Women's Association: harks back to an earlier pastoral Australia, where all hardships could be endured as long as there were expertly baked cakes and slices. Formed in the 1920s and a national organisation since 1945, the CWA is a volunteer-based support group dedicated to upholding the rural values of the pioneering generations, including traditional cooking. At one time, as seen by the advertisement above, the CWA operated retreat houses at reasonable rates to allow farm wives an affordable break from their endless toil and isolation. “A farmer works from sun to sun / But a woman’s work is never done.” Cricket: a) an insect like a cicada which makes a racket in the evening. b) the game of summer, which makes a racket in the arvo and, it is said, unites the nation. Don't try to understand it if you're from a non-cricketing country. Express mild interest and, if pushed to watch it, reflect that there are equally exciting games elsewhere in the world that don't go on for quite as long, such as baseball (if you're American), curling (Canadians and Scots), boules/petanque/bocce (southern Europeans), bowls (aged Australians) and shuffleboard (cruise ship passengers). The worst possible scenario is to be pinned in a corner by a cricket fan determined to explain the rules to you, at which point you will reflect on the hardships of being an expat. However, there is profit in making a close examination of the terminology, as it will give you some idea of what's going on. For example: -“Bowling a maiden over”: what happens when the handsome, wealthy cricketer meets a female fan after the game. -“Gone for a duck”: the universal quest for Chinese food after a long afternoon on the pitch. -A “googly”: trying to find personal details on the Internet about a favorite player, such as the sexually explicit videos featuring former bowler Shane Warne. -“Spin”: making excuses about the failure of your bowlers to get the other side out. -“Leg before wicket”: blocking a fellow player from depositing his big paycheque at the bank. -"Gone for six": often misunderstood by Kiwis, who believe it means a player stepping out for some afternoon delight in the middle of a long test match. Crook: not the high-profile businessman or politician who's fighting to keep out of jail, but how you feel when injured or sick. "Crook back mate?" you might be asked if you refuse to help a friend move house. In general, how things are when they’re not working properly.  Culture Cringe: the anxiety that is said to lurk behind the brash Aussie self-confidence. Maybe, worry the intelligentsia, the home scene is more Kath & Kim than Kultur? More Dame Edna than Delius? Maybe the Poms/Yanks/Italians/(insert nationality here) really are more sophisticated? “We were so terribly far away from where things were happening, in a tiny, frantic, intellectually isolated world, starving. Sidney Nolan had his first one-man show and a philistine flung a can of paint over his pictures. So, many of us left Australia to search elsewhere.” – George Johnston, writing in 1965 of his art-student days in Melbourne (p. 218) Traditionally, the cringe was urban Australia comparing itself with London; ergo, the culturati of the Antipodes flocked there to receive benediction from the older, sleeker, wiser place. In the book/miniseries “Come in Spinner,” set in Sydney during WWII, the wealthy Palm Beach resident cringed to some English visitors – apologising in advance for the quality of the symphony concert they were about to hear. Artists like Sidney Nolan spent most of their careers in England; having received the tick from the critics there, they were able to ply their trade, in Nolan’s case continuing to paint images that harked back to his homeland. Then, in 1972, “The Adventures of Barry McKenzie” heralded a new Australia self-confident enough to mock the clichés foreigners held of yobbo colonials in sophisticated London. The “Crocodile Dundee” movies of the 1980s were a logical sequel, satirising New Yorkers as weak like kittens compared with the quick-witted, free-wheeling Outback Aussie. Anxiety and insecurity… Visitors in earlier eras noted the intense curiosity that Australians had for the opinions of foreigners. For example, the German traveller Bernd Lohse wrote in the late 1950s:  "Since

my entry into

Australia it has been striking how each person

awaits my judgement – with some tension, part proud, part

defensive, part defiant. The ordinary man seems to think that the

newcomer is duty-bound to congratulate him personally for having

created a land of milk and honey… "Since

my entry into

Australia it has been striking how each person

awaits my judgement – with some tension, part proud, part

defensive, part defiant. The ordinary man seems to think that the

newcomer is duty-bound to congratulate him personally for having

created a land of milk and honey…"How is it that such a question, 'How do you like it here?', which is natural anywhere in the world and rouses little interest, can play such a simple and decisive role in Australia? And how is it that the newcomer is so guarded and stamped by his answer that it can decide for a long time –positively or negatively – how he will be accepted in his new environment?" That level of anxiety has passed. As with many Americans who can’t believe you’d turn down an opportunity to move to the USA, Australians feel confident they’re in the “lucky country,” as Donald Horne dubbed it way back in the 1960s. |

|

|

|

|

|

Contact me Return to home page